Suspicious Identities in the Victorian Age: from Children’s Weeklies to Criminal Cases in Kate Summerscale’s The Wicked Boy

Abstract: Kate Summerscale’s docufictions investigate the disruption of stable individual identity in the later Victorian era. By investigating notorious trials, she underlines issues of cultural change in the context of the period’s social practices and the emerging complexity of the individual in the context of law, medicine and popular culture. The Wicked Boy (2016) focusses in particular on a renowned case of moral deviance with a child culprit, which leads to a consideration of the Victorian literary market for working class boys and the pernicious influence of the penny dreadfuls with their glorification of criminal protagonists. The close relationship between textual consumption and identity at the basis of Robert Coombe’s trial foregrounds the suspicion of literature as being responsible for moral degeneration. Reflections also include the illustrated newspapers and the reports from the Old Bailey, which offer examples of visual storytelling and mediatic attention towards crime and deviant behavior.

Keywords: Criminal responsibility, Popular legal culture, Visual storytelling, Mass media, Penny dreadfuls, Spectacularization of crime

Résumé : Les docufictions de Kate Summerscale abordent la perturbation de l’identité individuelle stable à la fin de l’ère victorienne. En enquêtant sur les procès notoires, elle met en lumière des enjeux de changements culturels dans le contexte des pratiques sociales de l’époque et l’émergence de la complexité de l’individu dans le contexte du droit, de la médecine et de la culture populaire. The Wicked Boy (2016) se penche en particulier sur un cas célèbre de déviance morale concernant un enfant coupable, ce qui conduit à analyser le marché littéraire victorien à destination des garçons issus de la classe ouvrière de même que l’influence pernicieuse des penny dreadfuls en raison de leur glorification des protagonistes criminels. La relation étroite entre la consommation textuelle et l’identité au cœur du procès de Robert Coombe met au premier plan une vision suspecte de la littérature en tant que responsable de la dégénérescence morale. Cette analyse porte également sur les journaux illustrés ainsi que sur les rapports de l’Old Bailey, qui offrent des exemples de storytelling visuel et d’attention médiatique portée au crime et aux comportements déviants.

Mots-clés : Responsabilité criminelle, Culture juridique populaire, Storytelling visuel, Médias de masse, Penny dreadfuls, Spectacularisation du crime

Kate Summerscale’s docufictions present a legal perspective on Victorian judicial procedures and, at the same time, bring under discussion the social practices of the time. In representing notorious trials (Sherwin 4), the author investigates deep cultural conflicts and anxieties regarding individual identities, in particular focussing on cases of children and young adults. These symbolic legal dramas actually bring the larger Victorian society under cultural scrutiny and suspicion at a time when the development of the sciences of the mind and the emergence of forensic psychology contributed to develop a new conception of the individual.

Criminal law was born and is applied to guarantee justice; it can be seen as a social practice through which a society both defines or constructs, and responds to deviance or wrongdoing through specific procedural rules. At the end of the trial, the established social order and tenet prevail and everything is reconducted into the rule underlying the shared vision of life in the community. Yet, deviance “can only tautologically be defined by looking to criminal law itself” (Lacey and Wells 3), therefore, the trial stages competing social narratives. Within that context, techniques of mass communication usually permeate the press coverage of the case. “[L]aw’s stories and images and characters leach back into the culture at large. In this way, law is a coproducer of popular culture” (Sherwin 5), and popular culture can affect the representation of legal issues. Sometimes fiction and reality blur as they participate in the same symbolic order and invest habits of mind of a normative value.

In the context of criminal law, suspicion can be based on stereotyping as well as on incongruity (vs. reasonable suspicion), as it focusses on people who do not conform and “do not fit into the context in which they are observed” (Cownie, Bradney, and Burton 234). Summerscale illustrates this kind of suspicion as she investigates the disruption of the conception of the stable Victorian identity in young adults and children. Her 2008 docufiction, The Suspicions of Mr Whicher, presents the process of investigation of the 1860 Road Hill House Murder, which extends to an analysis of the impact of the appearance of the detective as a professional figure in Victorian society. In “perhaps the most disturbing murder of its time” (Suspicions xi), suspicion entered the Victorian house and created “a dark fable about the Victorian family and the dangers of detection” (Suspicions xi). The figure of the detective (the first were appointed by the Metropolitan Police in 1842) represented a violation of the middle-class home and ended up by exposing the corruption behind the façade of Victorian respectability and domesticity. Whicher’s investigation delved into the secret selves of the Saville family members, as well as of the Victorian family at large. This assault on the middle-class value of privacy “created an era of voyeurism and suspicion” (Suspicions xii) which affected the Victorian social and cultural fabric. The press coverage of the case revealed privacy as a suspicious locus for deviance and sin. The Saville murder impacted the social unconscious as it was considered evidence of degeneration and national decay (Suspicions 221). It detected suspicions of the murder of a four-year-old child by his sixteen-year-old sister, thus attacking the very foundations of the Victorian institution of the family. Domestic murder was a particularly disturbing crime, given the home’s symbolical implication of cultural norm at the basis of the time’s social structure.

From the perspective of the investigation, all the elements of the Road Hill House murder case derived from Whicher’s questions, i.e. his suspicions (Suspicions xii). Ultimately, he failed to present evidence, that is, “information (including testimony, documents and tangible objects) […] to prove or disprove the existence of an alleged fact” (Klamberg 3). Such information typically aims at positing a relationship between two facts, the facts in issue (factum probandum), or proposition to be established, and the evidentiary fact (factum probans), or material supporting the proposition (Klamberg 115). Therefore, his allegations remained confined to a potential crime, a conjecture which nonetheless infiltrated the Victorian milieu.

Suspecting Children

Summerscale’s next docufiction The Wicked Boy (2016) reports the case of the 1895 Plaistow murder. Thirteen-year-old Robert Coombes lived with his brother Nathaniel, aged twelve, and his mother in a working-class district in the docklands of East London; the father worked for a shipbuilding company and was often away from home, as in this specific circumstance. When his aunt discovered the murder, Robert confessed the crime in the following terms: “Ma gave Nattie a hiding on Saturday for stealing some food, and she said, ‘I will give you one too.’ Nattie said: ‘I will stab her. No, I can’t do it, Bob, but will you do it? When I cough twice, you do it.’ ‘I did do it. […] I did it by myself. […] I did it with a knife, and it is on the bed” (Wicked 40). The two brothers had then spent two weeks in the same house with their mother’s corpse, asking John Fox, their father’s former shipman—a simple man—to stay with them, because, as they said, their mother was away to visit relatives. During the days following the murder they spent their time in what were considered dangerous pursuits typical of the working-class leisure time, e.g., they went to the theatre and to a cricket game. Robert was arrested and brought to trial, and the case soon widened to an investigation of the rise in juvenile delinquency in nineteenth-century London.

The children living in the poorest areas of the city had no awareness of the principles underlying social behaviour and tried to cope with the difficulties of life, often committing crimes such as stealing, for instance (Duckworth 9). Arrests or legal interventions elicited little respect for the law and the restoration of social order, as the children did not understand the reasons for the sentences. Moreover, there was no separate court for young defendants; they were subjected to the official ritual of the law, but they were “too young to appreciate the solemnity of the occasion” (May 13). Therefore, “[t]heir uncontrolled existence” was linked to “social disorganisation and challenged the very foundations of ordered society” (Duckworth 20). The investigation into the causes of the increase in juvenile crime led to a change in the conception of childhood, which distanced itself from the Romantic idealisation of innocence and purity of the beginning of the century, as criminal children proved “the very reverse of what we should desire to see in a child” (Carpenter, Juvenile Delinquents 292). It also led to the recognition of the status of the child in the judicial system (May 7) with a consequent series of reforms.

In 1851, Mary Carpenter underlined that children could not possibly entertain criminal intent: “in consequence of the immature state of physical, mental, and moral powers [a child] cannot act with a ‘malus animus’ in the same sense that an adult can” (“Letter” 239).1 She was here following Blackstone’s principle of doli incapax (1796): “an infant cannot be found guilty of a felony; for them a felonious discretion is almost an impossibility in nature” (Blackstone 23). However, Blackstone also specified that “If it appears to the court and jury that […the child] was doli capax […] he may be convicted and suffer death” (23). This contributed to an ambiguous image of working-class children, either threatening social order (thus provoking suspicion) or as victims of its failings.

Robert and Nattie were both under fourteen and, therefore, according to the 1889 Children’s Act, they were considered children. Nevertheless, they were ascribed criminal responsibility if they could tell right from wrong, “by the strength of […their] understanding and judgement” (Blackstone 23-24), and they would be tried in the same way as adults: “In most cases the fact that the offence was committed suggested that the perpetrator possessed a guilty mind and therefore punishment was justified” (Duckworth 40). They could be subjected to all the main forms of punishment: capital conviction, transportation, and imprisonment. However, magistrates could decide to exercise a compassionate discretion and commute a harsh sentence to transportation or imprisonment. As a matter of fact, belonging to the category “juvenile” was not always easily determined since registration of births became compulsory only in 1875 (although it had been introduced in 1837), and the officers relied on the appearance of children in order to confirm their declarations of age.

The Coombes brothers underwent a preliminary hearing at the magistrates’ court in Stratford and then they were taken to the courthouse in West Ham Lane for the inquest. The case created a huge gathering outside the courthouse, and the various phases of the legal proceedings were widely covered by the press. At the time, newspapers became legal forums and clippings were usually included in the official documentation of the cases (Wiener 111). The interest the case created rendered it a popular legal culture trial and subjected it to a process of spectacularisation and criminal celebrity. Robert was in the same position as James Canham Read, the renowned criminal he had gone to see after his arrest in Southend one year previously and who had become a myth of popular culture, aligned with “the villains and the heroes in the penny dreadfuls that Robert liked to read” (Wicked 21). 2

At the time, during trials, the appearance and behaviour of defendants were scrutinised for evidence of guilt, in particular their physical reactions and responses to accusation, in the conviction of a connection between the visible body and the invisible mind. However, already in a 1824 article from The Edinburgh Review the arbitrariness of such a connection was denounced, as well as the load of suspicion thereby imposed upon the defendant (Marshall 70).

A defendant was not allowed to give evidence at their own trial until 1898, so Robert became an identity put on display in order to be interpreted. He became the embodiment of the Boy Murderer, who disrupted the Victorian idealised image of childhood and the representation of a dysfunctional behaviour which put under discussion the institution of the family and society in its entirety as well. The potentialities of such disruption from the acknowledged norm were relevant, as usually the murderers were adults, not children, and this could induce a moral panic (Springhall, Youth, Popular Culture 42) through a suspicion that addressed potentialities of deviation.

During the inquest and subsequently during the trial, Robert showed disturbed behaviour; he alternated moments of composure with others in which he quietly laughed, made grimaces, and moved his lips as if he were speaking to himself. The newspapers commented upon the evidentiary value of Robert’s body and differently interpreted this as a mocking of the proceedings or the evidence of a primaeval behaviour, in connection with the contemporary pseudo-scientific theories of physiognomy, which saw criminals as underdeveloped men akin to children, and psychological insights into the mind of children expressed by Henry Maudsley, among others, who underlined children’s proclivities towards evil.3 Moreover, Robert pleaded “Guilty” and then “Not guilty” revealing his confusion and creating an interest in the investigation of his unknown mind. The body’s narration contributes to law’s stories. However, “the guilt is visible only after a narrative has been created” (Marshall 71), therefore Robert entered Victorian legal discursive practices and his body became transfigured into the body social of young working-class boys. This took place at a double level: through the medical analysis of Robert’s mind and through considerations about popular culture and weekly publications’ narratives which were imposed upon the case.

The possible consequence of the social and cultural danger of deviance was contained by blaming the crime on the “pernicious” reading habits of working-class boys; Robert’s collection of penny dreadfuls was admitted as evidence at the trial as a source of instigation to commit crimes by their young readers. The mere possession of such publications was used as evidence in criminal trials and the mere suspicion of their pernicious influence equated with criminal intent; an 1892 case of a child’s suicide was ascribed to his temporary insanity caused by the reading of such stories (Springhall, Youth, Popular Culture 90 ff). This conviction was nurtured at the time by drawing from selected crime reports until it became self-fulfilling, hiding the fear of confronting the phenomenon of an urbanised and commercialised popular culture.

The label “dreadful” ascribed to these publications was created and spread by middle-class journalists embracing the defence of morality against popular taste, and at the same time creating a “permanent lower class or juvenile ghetto” (Springhall, Youth, Popular Culture 9).

This shifted the suspicion from Robert’s personal motives for the murder of his mother to the whole cultural atmosphere of Victorian society; in particular, it implied the first acknowledgement of a “mass,” a wide and increasing cultural group which included, on the one hand, young readers from the middle class and hardly literate readers as well, and, on the other, the existence of mass media publishing for the young, which catered to their escapist imagination from the strictures of Victorian society.

Suspecting Boys’ Weeklies

When laws are broken, the offender is culpable and deserves to be punished, in an analogy between criminal conviction and moral judgement (Lacey and Wells 9). Juvenile delinquency threatened middle-class values about home and family life, as well as conventional childhood behaviour. Crime was considered a social disease; it diffused “a subtle, unseen, but sure poison in the moral atmosphere of the neighbourhood, dangerous as is deadly miasma to the physical health” (May 18). The reason for the spread of the disease of criminality was identified in popular culture’s production of penny dreadfuls, which, together with the spread of illustrated newspapers, introduced a reflection on the “reality-shaping power of mass-marketed visual images” (Sherwin 6) that was taking place in the late Victorian period.

The end of the nineteenth century witnessed an increase in juvenile literature thanks to the technological advances of the times that allowed for a faster editorial process and distribution, and a removal of duty taxes that permitted a cheaper production. The first dreadfuls were inspired by the gothic novel and the Newgate Calendars,4 then the term came to refer to cheap boys’ periodicals and the stories changed into plots of adventure, crime, and punishment, connected to the contemporary novelistic production, sensation novels and detective mysteries (Anderson 53-54). They were usually accompanied by violent illustrations that visually appealed to the presumed gory taste of the working class. The genre was not initially aimed at the juvenile market, but when adult readers preferred other emerging publications, it was enthusiastically appropriated by the young as a form of escape literature.5 This kind of weekly publication was widespread from the 1840s to the 1900s and signalled a cultural turning point as it was the first example of mass media publishing for the young. Sheila Egoff has observed that “In format, illustration, content, and popularity, [penny dreadfuls] were matched only by the rise and influence of the comic book in the mid-twentieth century” (413). This interest helped initiate commercial enterprises in an emerging editorial market, which led to the commodification of popular culture and the beginning of a mediatised culture as well.

Working-class boys represented a new group of consumers who were economically independent, could purchase their own readings and looked for diversion from work in a kind of literature that exalted the capable young hero. They were called New Boys (Summerscale, Wicked Boy 90), in an analogy with the New Woman, as they were assertive and beyond control. The penny dreadfuls were held responsible for an increase in juvenile crime as they presented crime as an alternative to life in the community. The protagonists soon included characters that were similar to the readers, “The model hero [… who] throws up his clerkship, his post in the grocery or tailoring establishment, or his office of errand boy, and goes off on some impossible expedition and returns rich, radiant, triumphant, and scornful of common ways and occupations” (Dunae 134). This kind of cheap publication for working-class boys was accused of presenting a distorted vision of the world and a disrespect for authority, and was seen as “literary debauchery” (Dunae 140), thus betraying a fear of social disruption.

Robert Coombes’s prosecutors were Charles Gill and Horace Avory, the same who had prosecuted Oscar Wilde. This connection was complicit in considering the dreadfuls as “lower class equivalents of Wilde’s decadent productions” (Summerscale, Wicked Boy 107). As a matter of fact, Wilde’s trial cast moral suspicion on his work, which was accused of exerting a pernicious influence upon young men and promoting urban decadence against the value of middle-class respectability. In this blurring of boundaries between literature and life, in both Wilde’s and Coombes’s cases, literature was taken as evidence of a charge that affected the individual and widened to include the period’s cultural atmosphere. The defendant, surrounded by suspicion, became literature, and the victim became the body social. Notwithstanding the many instances in which the penny dreadfuls were connected to criminal cases, it remained impossible to prove such relationship of cause and effect, also because the penny dreadfuls were widespread among the boys of all social classes. Appeals to government legislation were made to suppress this kind of literature as it was believed to create a “poisonous addiction” (Vaninskaya 73), but they proved unable to demonstrate the connection between cheap literature and juvenile crime: “under existing laws, only publications that were blasphemous, obscene or seditious could be banned” (Summerscale, Wicked Boy 106). Therefore, the critics of the time decided to counter such editorial production with religious tracts and philantropic publications, as well as “penny healthfuls” both by religious associations and private mass-market publishers, in defence of the middle-class values of honesty and respectability, thus creating “a class tension between editorial idealism and commercial pressure” (Lang 23). An example of penny healthful is The Boy Detective (1865-1866), whose protagonist directly addresses the readers with specific references to the penny dreadfuls:

Boys, I am one of yourselves, and, like yourselves, have taken great delight in reading the dashing adventures of Pirates, Highwaymen, and Robbers, and have sometimes felt satisfaction when the bold thief has beaten the thief-taker. You will, in this story, see the other side of the picture, and will learn how a noble band of lads joined together to lend a helping hand to those who were tempted by poverty and hunger to become dishonest, and to hunt down the most terrible who dared to corrupt others by their villainy. Should you find as much pleasure in startling deeds of daring, performed in the cause of honesty, as you do in the courage of great robbers; if you acknowledge how noble how great and brave an honest thief hater may be, great is the reward of your loving comrade—Ernest Keen, the Boy Detective. (The Boy Detective 21)

This kind of Boy Hero, the antithesis of the Criminal Boy Hero, became suspicious because his adventures contained the same elements as the penny dreadfuls they aimed to counter, such as kidnapping, forgery, murder, and the protagonist occasionally transgressed both the law and social hierarchies.

The press and trial proceedings of the time continued to trace a connection between cases of juvenile delinquency and the reading of penny dreadfuls. The copies found in the houses of the young culprits were considered stimuli to dishonest conduct and vice. Sometimes, however, penny dreadfuls were conveniently indicted for young defendants’ criminal behaviour. As Summerscale posits, “Instead of ascribing the crime to causes such as social discontent, financial need or greed, innate depravity, it was ascribed to fantasies of violence inspired by fictional or real-life stories” (Summerscale, Wicked Boy 97). In essence, they acted as catalisers and cultural scapegoats to counter the fear of a social overthrow. This perspective was also supported by doctors’ testimonies during trials as they ascribed a possible cause for children’s moral insanity to an overactive imagination influenced by the adventures published in boys’ weeklies.

In Robert’s case, a similarity was found between his case and the adventures of a penny dreadful hero, Jack Wright, who travels around the world with two comrades, fighting opponents and looking for treasures. Usually, the protagonists were also forgers. Robert had actually falsified the signature of his father and planned to travel the world with Nathaniel and John Fox (Summerscale, Wicked Boy 16). After the jury’s verdict at the inquest, the following consideration was expressed: “We consider that the Legislature should take some steps to put a stop to the inflammable and shocking literature that is sold, which in our opinion leads to many a dreadful crime being carried out” (Summerscale, Wicked Boy 108)—which can be interpreted as a search for a legal sanctioning of this cultural accusation/suspicion.

During Robert’s trial it was established that “[p]ernicious literature would be worse for a boy who was suffering from a mental affection” (Old Bailey On Line), and Robert’s defensc pleaded insanity. The boy was described as more intelligent than the average boy of his age but characterised by forms of obsession and unspecified mental failures. As his father said, “if he read of a ghastly murder, his whole mind would seem to be absorbed in it. Nothing could divert him from it. […] After the spell passed, he would be a child again, as innocent and unsophisticated as anyone of his age” (Summerscale, Wicked Boy 69). This coexistence of eccentricities and mental brightness was ascribed to a certified “cerebral irritation” probably due to the process of his difficult birth. As Summerscale writes, “[t]he term implied a physiological basis for Robert’s condition but was in truth merely descriptive. It gave no real clues as to the cause of his disturbance, which could be anything from unhappiness to physical injury” (Wicked Boy 163). He was examined by the prison’s medical officer in order to ascertain his “wicked disposition,” and he was reported to be of unsound mental state. He complained of headaches and said he had heard voices urging him to kill his mother. Since 1843 temporary insanity had been admitted in the defence at trials. In the mid-Victorian period, medical testimony tended to connect moral consequences to a specific physical pathology affecting the ability to distinguish right from wrong, which was the basis for criminal responsibility and the distinction of childhood from adult age for a defendant. This also implied “the common law’s willingness to entertain a body of opinion that claimed unique insight into the mind of the mad” (Eigen, “Lesion of the will” 426), the mental contemplation of a crime. This led to the postulation of non-intentional behaviour, a suspension of human agency and impaired power of reasoning, called lesion of the will. “No longer restricted to confused intellect, insanity might instead be a matter of deranged conduct” (Eigen, “Lesion” 453), which was a complex concept for the court to deal with. Maudsley writes that “a disordered feeling is capable of actuating disordered conduct without consent of reason” (“A Discussion on Insanity” 770), thus disrupting the basis of criminal agency and responsibility.

The legal fiction of Robert’s insanity due to physiological motives was connected to the influence of the penny dreadfuls; this narrative was preferred to an investigation into the innermost dimension of the child’s identity, which, in the nineteenth century, was subject to mecialisation and discovered to be “prone to numerous nervous disorders” (Shuttleworth 3). The child came to occupy a central position in nineteenth-century discourses of selfhood, in the passage from their Roussovian idealisation to “a figure of pathology” (Shuttleworth 11) in the emerging disciplines of child evolutionary psychology and psychiatry. Children became social “others”; they were revealed to be “complex, frequently disturbed beings who [we]re liable to the full range of adult mental disorders. They [could] also commit those most seemingly adult of acts: murder and suicide” (Shuttleworth 360).6 Nonetheless, they remained at the centre of the domestic sphere and the family, the central institution in the English society,7 implicitly contesting its own assumptions.

Suspecting the Media

During the various phases of the trial, the judge tried to protect Robert and Nathaniel from mediatic attention, “from becoming a piece of street theatre, shielding them from the gaze of the public” (Summerscale, Wicked Boy 51). The murder of Emily Coombes quickly attracted dark tourism8 and the murder was continuously commented upon and re-enacted in the press. The papers reporting the trial were distributed very quickly outside the Old Bailey and “[a]lready the narrative of Robert Coombes’s crime had been published throughout the country, illustrated by artists and adapted for the stage” (Wicked Boy 148). The law was already turned into a spectacle as the crime was performed in visual media through “[f]amiliar images, popular story forms, and recurring symbols”(Sherwin 6).

People were attracted to the family’s house. Their morbid curiosity led them to visit the site of the crime in a sort of psychogeographic experience. Victorian dark tourists were also fascinated by the perpetrators (Edmondson 88), in an unconscious desire to celebrate crime and deviance, while the victims became dehumanised. This commodification of death was highly disturbing and disrupted public consciousness as it involved the encounter with the death of “significant others” (Seaton 11), in this case a mother.

The press became a space for contending ideologies and perspectives on class, gender, responsibility, for discussions about guilt and punishment (Wiener 110-125) in an “image-based manipulation of irrational desire, prejudice, and popular passions” (Sherwin 7). The criminal trial usually strengthens an accepted view of reality, but in notorious trials this is precisely what comes under scrutiny; the media then actively engage in “the concerted effort to deliberately construct preferred versions of (and judgments about) self and social reality” (Sherwin 7).

Newspapers reported the different phases in the trials of juvenile delinquents and contributed to creating their image in the popular imagination: “the nineteenth-century media created a culture more conversant with violent crime than any society of the previous century, or perhaps any society of any century” (Casey 390). Thanks to the development of the press in the nineteenth century the reports soon came to include illustrations and were organised with headlines and sensational language in the style of the New Journalism of the time. Journalists played the role of mediators between the judicial system and the public, creating courts of public opinion where the circumstances of the case were reported, as well as legal and psychological elements that could help the readers understand the procedures and the issues at stake. Crime news was devoted an important part of the papers, as it responded to the interest of the time in sensational news. Illustrators drew on standard constructions and representations of normative domesticity as a setting for the crimes, thus providing narratives which became part of the crime itself, rather than a mere record of it. Thus, they gave shape to the social unconscious, to suspicions regarding identities and social roles.

Illustrated newspapers fictionalised Robert’s case and transfigured it into a penny dreadful, depicting Robert as deviant and Nathaniel as vulnerable and powerless. In fact, as the inquest and the trial pointed out, he had conspired with his brother, had done nothing to prevent the murder and had escaped through the window when the policemen arrived.

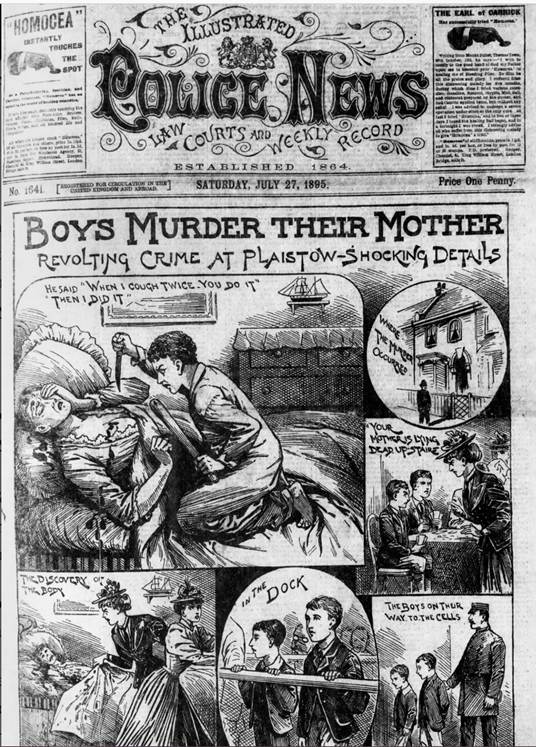

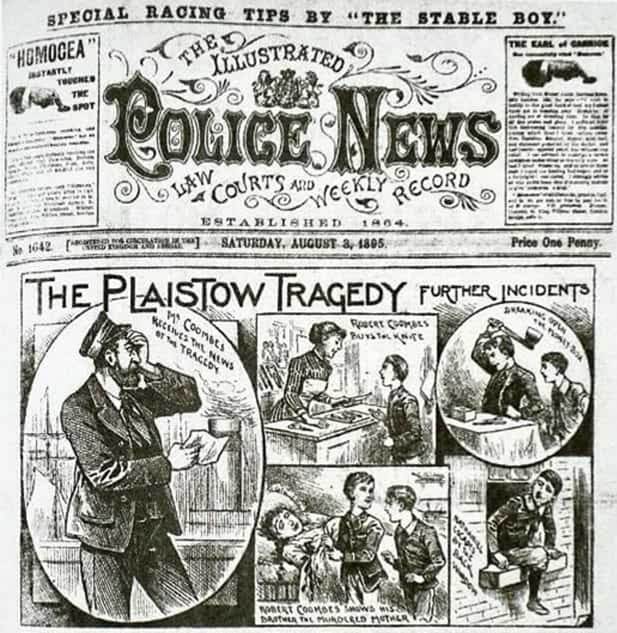

Among the periodicals of the time, The Illustrated Police News was considered a “sensational illustrated newspaper” (Smalley 56) and it encountered the same suspicion as the penny dreadfuls because its huge circulation could affect public morality with its sensational depiction of crimes. It was characterised by the presence of illustrations that, by 1868, filled the whole front page, presenting a visual storytelling of the crime. The newspaper was actually renowned for the precision and reliability of the images and its social commitment to promote a “fair and consistent sentencing of criminals, especially juveniles” (Stratmann, Shocks, Scandals 8). Stratmann writes that “once the cover became entirely pictorial, it had an impact which other papers could only try to emulate, and by including captions in the engravings the paper could provide banner headlines many years before they became possible in text-only newspapers” (Stratmann, Cruel Deeds 25). Interestingly, the newspaper did not incorporate photographs, as graphic images could better render the physiognomy of the protagonists and were more dynamic in the depiction of the scene, seemingly perpetuating an evidentiary reading of the bodies of the protagonists. This created the effect for the viewer of experiencing the events first hand. At the centre of the images was usually the moment of the crime or the discovery of the body: “the accused would be in a position of dominance or strength, standing over his victim, with a raised arm holding a weapon pointed threateningly at his target” (Smalley 123). The victim was usually unconscious or depicted with an expression of fear and pain. Blood was present in connection with wounds. Such representation of crime aimed at entertaining the readers and was often influenced by the melodramatic9 and theatrical gestures of the body and non-verbal signifiers, which short-circuited reason and affected the imagination of the observer. The newspapers also included illustrations of the trial and of the defendant. Under such conditions, the viewers became the investigators and/or the sanctioning audience of the legal process. At the same time, they experienced a cathartic involvement in the visual narrative of a collective horror. This kind of illustrated newspapers provoked “interest, fear and concern” (Archer and Jones 137) at one and the same time and proved to be “socially conscious” (Strattmann 8).

In The Illustrated Police News dated July 27, 1895 (Fig 1), the narrative of Robert’s case starts with the murder and ends with the delivery of the boys to their cells, presumably after the sentence. The images are preceded by a heading in capital letters, “Boys Murder their Mother. Revolting Crime at Plaistow—Shocking Details,” which sets the tone for the illustrations (See Figure 1). The emphasis is on the matricide, once again disrupting the innermost structure of the Victorian institution of the family, and on the child murderer. The larger image is devoted to the murder, and it stereotypically depicts Robert standing above his victim after stabbing her, with blood flowing from her chest. All his bodily muscles are tense and he is holding a weapon in each hand (the knife and the truncheon); his face is contorted and the eyes bulging in an atavistic image of violence and assault which recalls the features of Cesare Lombroso’s criminal man.10 This is countered by the representation of the brothers in court “in the Dock,” where they seem to be two ordinary children, possibly making the viewer doubt their guilt. The first illustration is accompanied by a rendition of Robert’s confession: “He said, ‘When I cough twice, you do it,’ Then I did it,” which captures the moment of Robert’s decision to act, the discriminating moment between right and wrong, and the usually ensuing acquisition of criminal responsibility. As said earlier, Robert’s defence used the insanity plea. According to the developing psychological theories of the time, it was possible to determine cases of partial insanity, that is, temporary delusions, if “at the time of committing the act, the party accused was labouring under such a defect of reason, from disease of the mind, as not to know the nature and quality of the act he was doing; or, if he did know, that he did not know he was doing what was wrong” (Smith 15). Robert was acknowledged as suffering from homicidal monomania, a kind of moral insanity that affect the emotions and, as Jean-Etienne-Dominique Esquirol theorised, provoked irresistible impulses followed by indifference and/or loss of memory (Esquirol 320). This condition underlines the shift in the legal construction of insanity from cognitive criteria to volition and unconscious behaviour.11 Robert was declared guilty but insane: a medical condition was fashioned into legal criterion and the “diagnosis of insanity […] inserted homicide into its own name” (Eigen, “Diagnosing Homicidal Mania” 434). The final illustration depicts the moment when the boys are accompanied to their cells by a policeman representing law and order, with the following caption: “The boys on their way to the cells.”

The issue dated August 3, 1895 (Fig. 2), presents a visual narrative reconstruction of the events in a melodramatic style. In particular, Robert’s premeditation is suggested as he is represented buying the murder weapon, then “breaking open the money box,” that is, the economic reasons for the murder, and “show[ing] his brother the murdered mother,” that is, the revenge motive for the murder. Summerscale reports that Dr Bourneville12 became interested in the case and although he ascribed the murder to atavistic impulses, following Lombroso’s theories, the elements which indicated a possible premeditation could not coexist with a mentally primitive development and the hypothesis of degeneration (Wicked Boy 90-91), thus casting doubt on the public narrative of the case.

The images in TheIllustrated Police News are juxtaposed following the associationist procedure of visual storytelling; the juxtaposition of panels also keeps the actions separate, to be connected through the viewer’s participatory imagination. The viewer/reader constructs a story moving from panel to panel, and each panel can be approached focussing on different aspects: the story, the picture, and the whole narrative sequence, thus leading to a reconstruction of the murder and its aftermath (Stein and Thon 33). The full-page images of the illustrated newspapers were usually collected and hung on the walls by the readers, promoting a vicarious experience of the crime. The illustrations managed to catch what was seemingly not admissible in court, that is, a double narrative about Robert’s identity, “both scheming and desperate, ruthless and lost, in which he both knew and did not know what he had done and why he had done it” (Summerscale, Wicked 148). In the illustrations we can see the indictment of Nathaniel, sharing the premeditation of the murder, while the charges of being accessory to the fact were withdrawn at the Old Bailey and he subsequently appeared as a witness against his brother. As Summerscale observes, “None of the lawyers pressed Nattie on whether it was he who had urged Robert to kill their mother […]. He did not explain why he had colluded with Robert’s plan to kill her, nor did he acknowledge the act that prompted the murder” (Wicked Boy 93). He was aware of the lies told by Robert before the discovery of their mother’s body. It is as if the most disturbing aspects of the case were subsumed into a more controllable narrative, but they emerged in visual popular culture and became part of the collective unconscious by giving form and shape to suspicions of children.

Conclusion

While awaiting the beginning of the trial in prison, Robert wrote a letter to Reverend Shaw, the curate of the church the Coombes family regularly attended, which contained the following information: “[…] I think they will sentence me to die” (Summerscale, Wicked 131). The letter was accompanied by two pictures: in one, titled “Scene I—Going to the Scaffold,” three figures walked towards the gallows and upon the first one was written “Executioner;” in the other, titled “Scene II—Hanging,” a body hung from the gallows and the following words issued from his mouth: “Goodbye; here goes nothing! P. S. Excuse the crooked scaffold. I was too heavy, so I bent it. I leave you £ 5,000” (Summerscale, Wicked 131).

Robert presents a visual description of his situation and the expected outcome of the trial, in a style that recalls the penny dreadfuls, and stages the punishment instead of the celebration of the criminal. Illustrated newspapers very rarely represented the sentencing of a child, and often the sentence was commuted; Robert seems to transgress this final boundary, once again giving shape to it through its visual representation, and at the same time mocking the whole judicial system.13

The Plaistow murder case reveals how suspicion surrounded the emergence of working-class youth culture rather than juvenile crime. The narratives provided by the penny dreadfuls superimposed themselves on the narrative of the law—when Nathaniel gave evidence against Robert, he ascribed the cause of the murder to a desire for adventure, going to an island, drawing it from the stories they used to read—and brought the cultural milieu under scrutiny. Moreover, the inscrutability of the culprit led to suspicions about children murderers, only to contain them by shifting such suspicions to the contemporary consumption of penny dreadfuls, in a mediatisation of crime and of criminal responsibility that shook the entire society.

Notes

- 1With regard to this, also see Taylor 63.

- 2Read had killed a twenty-three-year-old dressmaker because she threatened to reveal their relationship and expose the multiple facets of his identity against his respectable façade as a family man. Read denied the charge until his execution. He acknowledged the interest of the crowd/audience and “stopp[ed] to shake hands with people who had assembled outside” (Wicked 21). His self-control was remarked upon and amplified by the newspapers: “Few doubted Read’s guilt, observed The Evening News, but his ‘nerve,’ his ‘cool, yet daring’ demeanour and his ‘keen and bright intelligence’ won the admiration of many” (Wicked 21).

- 3See The Pathology of Mind: “The thoughts, feelings and habits of boys and girls when they are together and not under suspicion of supervision are hardly such as a prudent person would care to discover in order to exhibit proof of the innate innocence though he might watch them curiously as evidence of innate animality of human nature” (385).

- 4The Newgate Calendars were prison calendars reporting memoirs of the inmates before their trial and/or execution. They were intended as moralistic publications and showed the efficiency of the penal system, however their sensational content rendered them sources for the so-called Newgate novels and detective fiction. (Worthington)

- 5This was favoured also by the increase in literacy provoked by the 1870 Education Act.

- 6One of the first cases reported in the Journal of Mental Pathology and Psychological Medicine, founded in 1848, was a 12-year-old child murderer who at the trial was declared of unsound mind. The case grounded the possibility of insanity in young children (Shuttleworth 28-29).

- 7As Shuttleworth quoting Connolly observes, “While the disruptive children of the poor are speedily sent to asylums […] those of the upper classes are kept behind closed doors” (Shuttleworth 33).

- 8“Dark tourism” refers to tourism to sites associated with tragedies, death and disaster. The first instances of dark tourism are actually dated 1888, in connection with the Whitechapel murders (de Simine 54).

- 9“As the dominant theatrical mode of the first half of the nineteenth century, melodrama operated within a clear moral framework, and seemed to offer a rigidity and moral certainty that could counteract the crime of domestic drama” (Walsh 13).

- 10According to Lombroso’s theory on the criminal man, the morally insane offenders are characterized by a specific physiognomy, for example large jaws, facial asymmetry, unequal ears, etc. (Lombroso 214)

- 11This identified derangement of feelings or volition as the cause of crime, not culpability based on a willfully chosen action (Eigen, Mad-Doctors 57-60). Therefore, “insanity was a question of volitional control, not conscious awareness of the wrong being committed” (Eigen, Mad-Doctors 174). This shows how “criminal trials display very public choices about the value society attributes to individual actions” (Smith 7) and how “trials were occasions for expressing theories of human nature and associated value systems” (Smith 8).

- 12Désiré-Magloire Bourneville was a French neurologist that advocated care for children with physical or intellectual disability (Gómez-López et al.)

- 13Robert was not sentenced to death but to indefinite detention at Broadmoor Lunatic asylum. He remained there for seventeen years, until 1917. Then he became a soldier during the First World War and then moved to Australia, leading a quiet but successful life, and also acting as a foster parent for an abused child. His personality has remained inscrutable over time, as inscrutable as his responsibility in the murder.

Bibliography

- AA. The Boy Detective; or The Crimes of London. A Romance of Modern Times. Newsagents’ Publishing Company, 1866.

- Anderson, Vicki. The Dime Novel in Children’s Literature. McFarland & Company, 2014.

- Archer, John and Jo Jones. “Headlines from History: Violence in the Press 1850-1914.” The Meanings of Violence. Edited by Elizabeth Stanko. Routledge, 2003.

- Blackstone, William. Commentaries on the Law of England. Book IV. University of Chicago Press, 1979.

- Burrow, Merrick. “Oscar Wilde and the Plaistow Matricide: Competing Critiques of Influence in the Formation of Late-Victorian Masculinities.” Culture, Society and Masculinities, vol. 4, 2012, pp. 133-147.

- Carpenter, Mary. Juvenile Delinquents. Their Condition and Treatment. Cash, 1853.

- Carpenter, Mary. “A Letter from Mary Carpenter, 5 February 1857.” Parliamentary Papers, vol. 33. Geirge E. Eyre and William Spottiswoode, 1857, pp. 238-240.

- Casey, Christopher A. “Common Misperceptions: The Press and Victorian Views of Crime.” Journal of Interdisciplinary History, vol. 41, no. 3, 2010, pp. 367-391.

- Cownie, Fiona, Anthony Bradney, and Mandy Burton. English Legal System in Context. Oxford University Press, 2013.

- Crofts Penny. Wickedness and Crime. Laws of Homicide and Crime. Routledge, 2013.

- de Simine, Arnold. Mediating Memory in the Museum: Trauma, Empathy, Nostalgia. Macmillan, 2013.

- Dickens, Charles. Oliver Twist. 1837. Penguin, 1985.

- Duckworth, Jeannie. Fagin’s Children. Criminal Children in Victorian England. Hambledon and London, 2002.

- Dunae, Patrick A. “Penny Dreadfuls: Late Nineteenth-Century Boys’ Literature and Crime.” Victorian Studies, vol. 22, no. 2, 1979, pp. 133-150.

- Edmondson, John. “Death and the Tourist: Dark Encounters in Mid-Nineteenth-Century London via the Paris Morgue.” Palgrave Handbook of Dark Tourism Studies. Edited by Philip R. Stone et al. Macmillan, 2018, pp. 77-102.

- Egoff, Sheila. “Precepts, Pleasures, and Portents: Changing Emphases in Children’s Literature.” Only Connect: Readings on Children’s Literature. Edited by Sheila Egoff et al. Oxford University Press, 1980.

- Eigen, Joel Peter. “Lesion of the will: Medical Resolve and Criminal Responsibility in Victorian Insanity Trials.” Law & Society Review, vol. 33, no. 2, 1999, pp. 425-459.

- Eigen, Joel Peter. “Diagnosing Homicidal Mania: Forensic Psychiatry and the Purposeless Murder.” Medical History, vol. 54, no. 4, 2010, pp. 433-456.

- Eigen, Joel Peter. Mad-Doctors in the Dock. Defending the Diagnosis 1760-1013. Johns Hopkins University Press, 2016.

- Esquirol, Jean-Etienne-Dominique. Mental maladies; A Treatise on Insanity, Lea and Blanchard, 1845.

- Garner, Brian A., ed. Black’s Law Dictionary. 1891. 8th edition. Thomson West, 2004.

- Gómez-López, Mariana Teresa et al. “Désiré-Magloire Bourneville and his Contributions to Pediatric Neurology.” Arquivos de Neuro-Psiquiatria, vol. 77, no. 4, 2019.

- Klamberg, Mark. Evidence in International Criminal Trials. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, 2013.

- Lacey, Nicola and Celia Wells. Reconstructing Criminal Law. Butterworths, 1998.

- Lang, Marjory. “Childhood’s Champions: Mid-Victorian Children Periodicals and the Critics.” Victorian PeriodicalsReview, vol. 13, no. 1/2, 1980, pp. 17-31.

- Lombroso, Cesare. Criminal Man. 1887. Duke University Press, 2006.

- Marshall, Bridget M. The Transatlantic Gothic Novel and the Law 1790-1860. Routledge, 2016.

- Maudsley, Henry. The Pathology of Mind. Macmillan, 1895.

- Maudsley, Henry. “A Discussion on Insanity in Relation to Criminal Responsibility.” The British Medical Journal , Sep. 28, 1895, vol. 2, no. 1813, pp. 769-773.

- May, Margaret. “Innocence and Experience: The Evolution of the Concept of Juvenile Delinquency in the Mid-Nineteenth Century.” Victorian Studies, vol. 17, no. 1, 1973, pp. 7-29.

- Old Bailey Online, 1895. https://www.oldbaileyonline.org/print.jsp?div=t18950909-720. Accessed November, 29 2023.

- Seaton, Tony. “Encountering Engineered and Orchestrated Remembrance: A Situational Model of Dark Tourism and Its History.” Palgrave Handbook of Dark Tourism Studies. Edited by Philip R. Stone et al. Macmillan, 2018, pp. 9-32.

- Sherwin, Richard. When Law Goes Pop. The Vanishing Line between Law and Popular Culture. The University of Chicago Press, 2000.

- Shuttleworth, Sally. The Mind of the Child: Child Development in Literature, Science and Medicine, 1840-1900. Oxford University Press, 2010.

- Smalley, Alice. Representations of Crime, Justice, and Punishment in the Popular Press: A Study of the Illustrated Police News, 1864-1938. PhD thesis, The Open University, 2017.

- Smith, Roger. Trial By Medicine: Insanity and Responsibility in Victorian Trials. Edinburgh University Press, 1981.

- Springhall, John. “‘Disseminating Impure Literature’: The ‘Penny Dreadful’ Publishing Business Since 1860.” The Economic History Review, vol. 47, no. 3, 1994, pp. 567-584.

- Springhall, John. Youth, Popular Culture and Moral Panic. Macmillan, 1998.

- Stein, Daniel and Jan Noël-Thon, eds. From Comic Strips to Graphic Novels. Contributions to the Theory and History of Graphic Narrative. Degruyter, 2015.

- Stratmann, Linda. Cruel Deeds and Dreadful Calamities: The Illustrated Police News 1864-1938. British Library, 2011.

- Stratmann, Linda. The Illustrated Police News. The Shocks, Scandals & Sensations of the Week 1864-1938. British Library, 2019.

- Summerscale, Kate. The Suspicions of Mr Whicher. Bloomsbury, 2008.

- Summerscale, Kate. The Wicked Boy. Bloomsbury, 2016

- The Times, March 31, 1870, 10.

- Taylor, David. Crime, Policing and Punishment in England, 1750-1914. Macmillan, 1998.

- Vaninskaya, Anna. “Learning to Read Trash: Late-Victorian Schools and the Penny Dreadful.” The History of Reading. Evidence from the British Isles, c. 1750-1950. Vol. 2. Edited by Katie Halsey and W. R. Owens. Macmillan, 2011, pp. 67-83.

- Walsh, Bridget. Domestic Murder in Nineteenth-Century England. Literary and Cultural Representations. Routledge, 2014. E-book 2016.

- Wiener, Martin. “Convicted Murderers and the Victorian Press: Condemnation vs Sympathy.” Crimes and Misdemeanours, vol. 1/2, 2007, pp. 110-125.

- Worthington, Heather. “From the Newgate Calendar to Sherlock Holmes.” A Companion to Crime Fiction. Edited by Charles J. Rzepka and Lee Horsley. Blackwell, 2010, pp. 13-27.

About the author(s)

Biographie : Sidia Fiorato est professeur associée de littérature anglaise à l’université de Vérone. Sa recherche porte sur le droit et la littérature, le roman policier, la littérature et les arts de la scène, le conte de fées, les études shakespeariennes, les études de genre et les humanités médicales. Parmi ses publications figurent Performing the Renaissance Body: Essays on Drama, Law and Representation (en co-direction avec John Drakakis, Degruyter 2016), des articles sur la fiction policière et le conte de fées postmoderne. Elle est membre du Comité éditorial de la revue Pólemos: Journal of Law, Literature and Culture.

Biography: Sidia Fiorato is an Associate Professor of English Literature at the University of Verona. Her research interests include law and literature, detective fiction, literature and the performing arts, the fairy tale, Shakespeare studies, gender studies, the medical humanities. Among her publications are Performing the Renaissance Body: Essays on Drama, Law and Representation (edited with John Drakakis, Degruyter 2016) as well as essays on detective fiction and the postmodern fairy tale. She is a member of the Editorial Board of the journal Pólemos: Journal of Law, Literature and Culture.