Reading the Changing Deserts of the American West: Perception and Reality

Abstract: The vast, arid deserts of the American West traverse large-scale geographical landscapes.

Inhabitants write and re-write the ever-changing narratives of the West. Ways of living,

recreating, diverting water, and developing land have impacted the way these deserts

thrive, the way we connect with them, and the way we threaten them. These western

deserts are paradoxical on many levels: public open spaces that invite private interior

experiences, empty yet teeming with life, arid or flooded, freezing cold or burning

hot, human and geological, imagined and literal, windy and silent, wild yet tamed,

fenced-in yet boundless, iconic yet unknown, natural yet monumental, remote yet sometimes

politically charged. My interdisciplinary study explores the desert’s changing, paradoxical

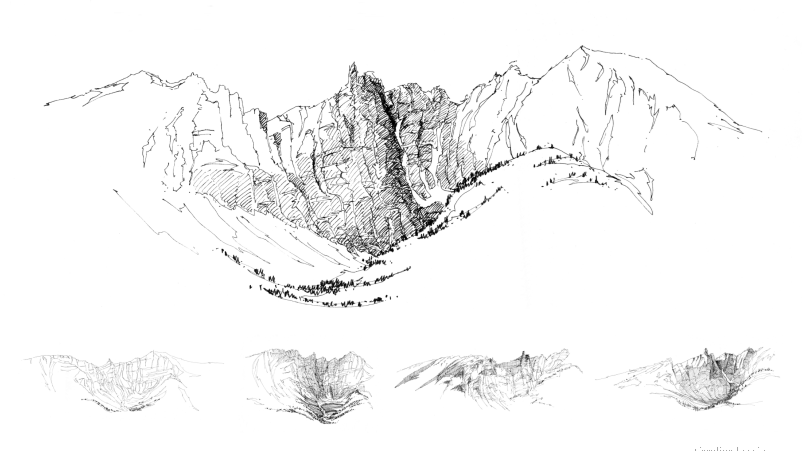

narratives in text and image. My drawings and photographs offer a visual representation

of the qualities and challenges of the desert landscape and the everyday life of its

inhabitants, discussed in three sections: scientific context, the imaginary, and sensory

perception.

Scientific context. This section explores the larger context—using scientific and

other lenses, as well as my own background. I lean on François Duban’s description

of how different professional lenses—from the geographer’s to that of the ecologist—establish

different definitions of ecosystems, depending on how interactions between humans

and landscapes are viewed.

The imaginary. Second, I delve deeper into the imaginary (including collective memory,

controversy, and culture). I turn the lens on the scale and aridity of the desert

as a source of inspiration. This article explores the colors and textures of the ever-changing

desert and considers the imaginary in diverse desert narratives, at both the individual

and the collective levels. Drawing helps explore these human interactions and distill

collective memories.

Sensory perception. Finally, I explore the experience of the desert through drawing,

including phenomenological experience and sensory perception. My sensory perception

internalizes all these conditions. The visual aspect of this project explores the

perceptual qualities of the desert under different conditions (silence, wind, hot,

cold, etc.). I conclude that drawing or viewing drawings of the desert in this context

helps all of us establish the link between perception and reality, and allows us to

experience the evolving desert environment.

Keywords: Drawing, Sensory perception, Collective memory, Imaginative perception, Deserts

Résumé : Les vastes déserts arides de l’Ouest américain traversent des paysages géographiques

à grande échelle. Les habitants écrivent et réécrivent les récits en constante évolution

de l’Ouest. Les modes de vie, de recréation, de détournement de l’eau et de développement

des terres ont eu un impact sur la façon dont ces déserts prospèrent, sur la façon

dont nous nous connectons avec eux, ainsi que sur la façon dont nous les menaçons.

Ces déserts de l’Ouest sont paradoxaux à plusieurs égards : vides mais grouillants

de vie, espaces publics ouverts qui invitent à des expériences intérieures et privées,

arides ou inondés, glaciaux ou brûlants, humains et géologiques, imaginaires et réels,

venteux et silencieux, sauvages mais apprivoisés, clôturés mais sans limites, emblématiques

mais inconnus, naturels mais monumentaux, lointains mais sous les projecteurs de la

politique. Mon étude interdisciplinaire explore cette question et les récits changeants

et paradoxaux du désert en texte et en image. Mes dessins et photographies proposent

une représentation visuelle des qualités et des enjeux du paysage désertique et de

la vie quotidienne de ses habitants, abordés dans trois sections : le contexte scientifique,

l’imaginaire, et la perception sensible.

Le contexte scientifique. Ici j’explore le contexte plus large–en me servant de l’optique

scientifique ou autres, ainsi que de mon propre parcours. Duban (1997) décrit comment

différentes optiques professionnelles établissent différentes définitions des « écosystèmes »,

de l’optique du géographe à celle de l’écologue, en fonction de la manière dont elles

perçoivent les interactions entre humains et paysages.

L’imaginaire. Ensuite, j’interroge l’imaginaire (y compris la mémoire collective,

la controverse et la culture). Je dirige mon objectif sur l’échelle et l’aridité du

désert comme source d’inspiration. J’explore les couleurs et les textures du désert

en constante évolution et considère l’imaginaire dans divers récits du désert, tant

au niveau individuel que collectif. Le dessin permet d’explorer ces interactions humaines

et de distiller des souvenirs collectifs.

La perception sensible. Enfin, nous explorons l’expérience (y compris l’expérience

phénoménologique et la « perception sensible ») à travers le dessin. Ma perception

sensible intériorise toutes ces conditions. L’aspect visuel de ce projet explore les

qualités perceptuelles du désert dans différentes conditions (silence, vent, chaud,

froid, etc.). Nous concluons que dessiner ou regarder des dessins du désert dans ce

contexte nous aide tous à faire le lien entre la perception et la réalité, et à faire

l’expérience de déserts en constante évolution.

Mots clés : Dessin, Perception sensible, Mémoire collective, Imaginaire, Déserts

The present study explores the question of interdependence and the desert’s changing, paradoxical narratives in text and image. As a landscape architect, visual thinker, and artist, I offer a unique perspective to this volume. I look at new ways of perceiving the desert. My drawings and photographs offer a visual representation of the qualities and challenges of the desert landscape and the everyday life of its inhabitants, discussed in three sections. First, I touch on the larger context and the different lenses through which we may view the desert. Second, I delve deeper into the imaginary (including collective memory, controversy, and culture). Finally, I explore the experience of the desert (including phenomenological experience and the concept of sensory perception) through drawing.

The vast, arid deserts of the American West traverse large-scale geographical landscapes. Inhabitants write and re-write the ever-changing narratives of the West. Ways of living, recreating, diverting water, and developing land have impacted the way these deserts thrive, the way we connect with them, and the way we threaten them. These western deserts are paradoxical on many levels: public open spaces that invite private experiences, empty yet teeming with life, arid or flooded, freezing cold or burning hot, human and geological, imagined and literal, windy and silent, wild yet tamed, fenced in yet boundless, iconic yet unknown, natural yet monumental, remote yet sometimes today politically charged.

But who and what defines the desert landscapes of the USA?

One way to approach deserts is to see them as either inhabited or uninhabited. Some scholars define deserts in the mythical sense, describing their qualities of intense heat and their aridity or highlighting the absence of humankind, which at first sight could fit the description of the “déserts du Nouveau Monde” by Sophie Bobbé (9). Bobbé also points out that some deserts contain life that adapted to these conditions, which makes those deserts reappear full of life when rain comes. These floras and faunas adapted; in a similar way, generations of Native American communities also adapted to the environment. Yet, François Duban points out (17) that some eminent geographers would not apply this core description of a desert to the Great Basin because it is inhabited (by humans) and has access to some water, thus it is not part of our mythical image based on the Sahara. The way out, as he suggests, is to use the foundations of ecological science to define deserts delineated by agreed upon systemic ecosystems (“écosystèmes systémiques”). I consider the Great Basin as a true desert and a desert that I myself am part of, living in the cold high desert plateau of Northern Utah. The Great Basin was originally constituted by a series of small early settlement communities of European descent cohabiting with Native American communities.

The desert of our imagination

The deserts of the American West in the United States share a narrative that is part imagination, part myth, part reality, and sometimes part controversy. Images from film, popular culture, literature and the past influenced what we think of as the US desert landscapes. The desert has long been part of pop culture from the western landscapes of cowboy movies to the red rocks of children’s Road Runner cartoons. Take iconic actor John Wayne’s films, for instance. Some of his westerns were filmed in the Southern Utah desert near Kanab and in Monument Valley. His movies enhanced certain parts of the Great Basin. “He dominated movies like a national monument dominates the landscape. His image worked its way into the American consciousness as a metaphor for America itself” (Zentner, see weblink). John Wayne movies formed our imagination of what the desert contains. The animated Road Runner and coyote, with falling rocks, and long, empty roads, are part of this narrative of the imaginative qualities of the desert, showing on screen its landforms with its extreme dry climate. In our imagination, inhabited by fictional road runners and coyotes, cowboys—and more importantly, by real Native Americans with a real understanding of the landscape—we see its landforms and rocks, vegetation, water sources.

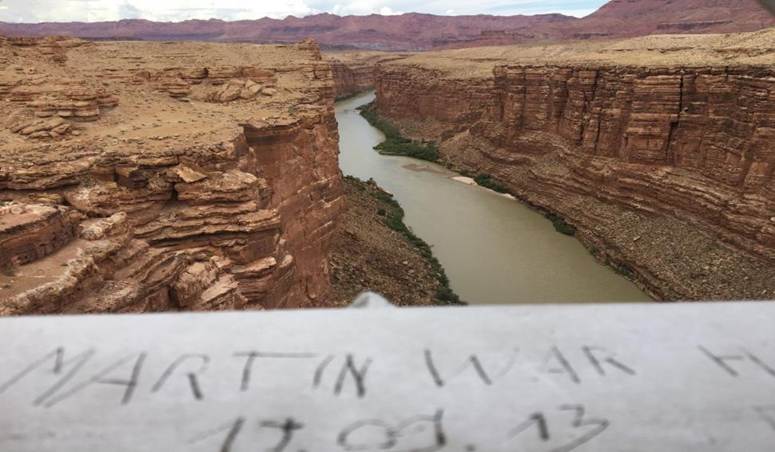

Marble Canyon: an ever-changing desert

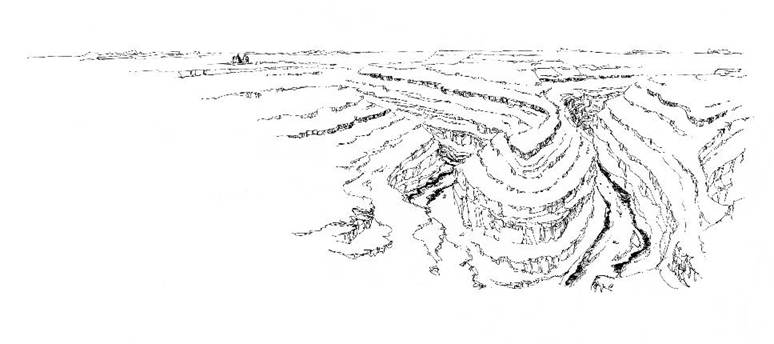

The desert is ever changing, both in its physical appearance and in our imagination. Water plays an important role in this aspect. A specific example of a site will prove useful here. In Marble Canyon, Arizona, where the Colorado River water flows, we see the process of erosion along the canyon and the effect of damming south of Lake Powell (see figure 1). The desert also changes constantly in both its reality and our perception of it. Terry Tempest Williams poses the question, “Can we change America’s narrative of independence to one of interdependence—an interdependence beautifully rendered in the natural histories found in our public lands?” (The Hour of Land 12).

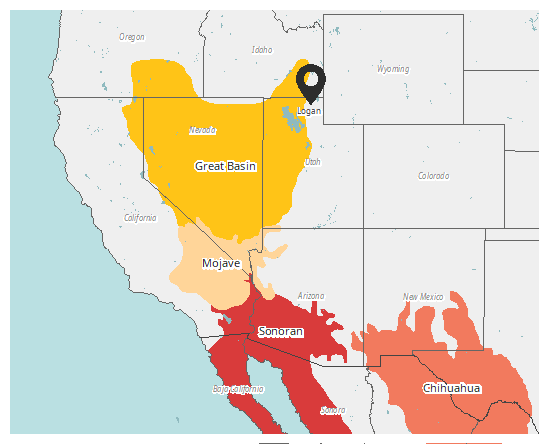

Scientific context: how to define the Southwestern deserts of the USA

As can be seen throughout this volume, there are many ways to look at and define the desert. In the content of this article, I will look at just some of the lenses through which we view and describe the desert from the scientific to the artistic. One significant and helpful way to define deserts is at the bioregional scale. When doing so, we avoid the discussion of (often artificial) political boundaries. There are four deserts corresponding to four bioregions in the Southwest of the United States and Northern Mexico (see figure 2). Those are the Great Basin, Mojave, Sonoran, and Chihuahuan deserts.

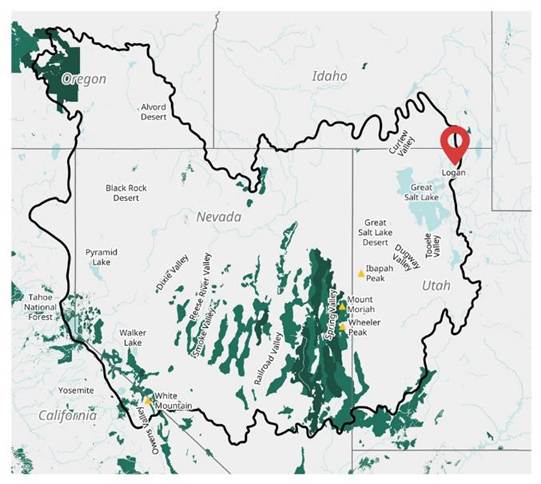

From these four bioregions, we can look at larger bioregions of North America as they traverse Canada, the USA, and Northern Mexico to get a more complex mapping of all deserts. From those bioregions, we move to a more intricate classification that differentiates cold versus hot deserts, namely ecoregions (see figure 3). Doing so reveals that most of the deserts are actually inhabited and do have a certain amount of rainfall, also showing the regions of aridity based on available water.

What defines deserts thus depends on the lens through which the viewer looks, from the objective of the territory defined by its ecoregion. In addition, which boundaries and which lens one uses to describe the desert depend on one’s professional interest and training. The geologist may be concerned with the nature of the material and the geological processes in how the desert came to be at different times in geological history. The geographer may be concerned with the relationships of humans, exploring how the desert is inhabited or whether it is uninhabited. In turn, the geomorphologist may be more interested in how the desert came to be by a process of millions of years and what forces (water, wind, volcanoes) played a role. The ecologist or biologist may be more interested in the desert relationship to living organisms, also going back millions of years. The ethnologist may be more concerned with understanding what relationships Ancestral Puebloans and the desert had with each other. Writers or filmmakers may certainly be inspired by the desert, providing cinematic images and/or written accounts. Artists may be preoccupied with imbuing or marking the desert by creating interpretative messages or by responding to certain visual processes as they perceive and experience the desert. Landscape architects may be mostly preoccupied with the relationship that living and inhabiting communities have with their environment and how one may intervene in that particular landscape. From this latter point of view, my thoughts on the desert are about understanding, planning, and designing for its future.

Stephen Trimble shows us (13) that boundaries can be fluid, which is also dependent on lens and aspects one chooses to define the desert. He highlights how four aspects can lead to four conceptions of the Great Basin: “hydrographic, physiographic, historic, and ecologic,” with all four of them contributing “to its reality” (see figure 4). Looking through those lenses, the boundaries are defined through the complexities of the landforms of mountains and ranges with their folds and orientation, watersheds with rivers and lakes, the long history of their formations, and certainly how they all connect to other places outside of political boundaries. Describing the Great Basin Desert in such a way informs us of its physical and contextual characteristics; that is, the subjective, rather than an objective, region. Mapping and focusing on the relationships of mountains and ranges and bodies of water opens possibilities for an enriched way of seeing and perceiving deserts.

Through drawings, we are able to better get at the subjective, the experiential, the imaginative and sensory perception of the desert.

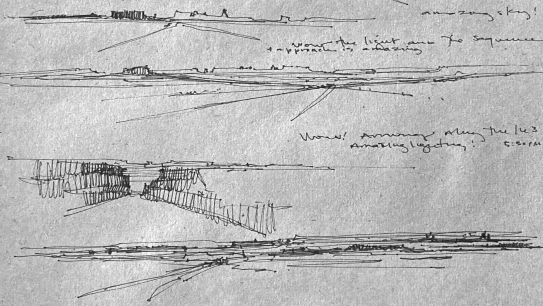

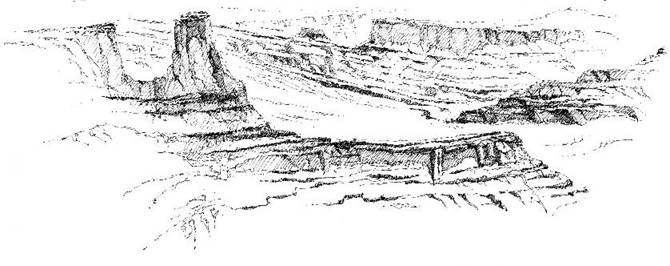

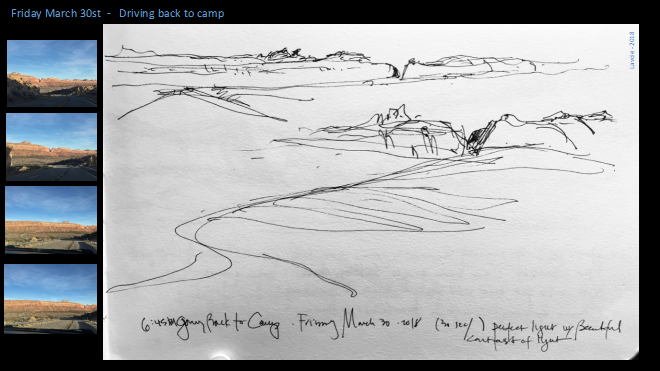

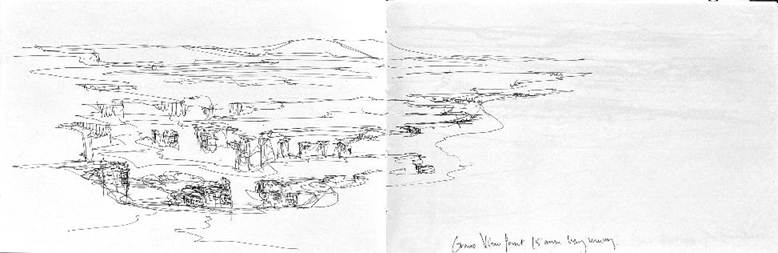

In my view, the desert emphasizes distance, openness, and vast skies—with the sky being the most important element of perception. The drawings and the photograph in figures 5, 6, and 7 show the immense scale of the desert in Southern Utah. For any artist, this is an inspiring perspectival view with a delicate vanishing line. My drawings accentuate, yet simplify, those qualities while highlighting the vastness and the distance covered by the desert roads, with tunnels cutting through the mountains (see figure 5).

Highlighting the contrasts

Drawings such as those featured here seek to highlight the multitude of contrasts in the deserts and arid regions of the Western United States. People are fascinated, for instance, with the contrast of vast geological time and the short human experience. That is why we are drawn to the desert as tourists or for different forms of recreation. Such contrasts, listed below, also highlight problematic or polemic aspects of the desert:

Extreme temperatures: cold nights / hot days with harsh sun

Water / drought effect on landscape and on people

Objective geological time / subjective human time experience

Objective geographic scale / subjective human scale

Desert plateau/ fertile valleys or irrigation systems

Wilderness area / overpopulation and overuse of resources

Like Terry Tempest Williams, as a resident of the desert, I focus on and seek to understand the interrelationships and human interactions in and around the desert landscape. Describing the making of a desert, Stephen Trimble cites John Steinbeck’s perception (from Travels with Charley, 1962) of this inter-connectiveness of processes, at a different timescale, so relevant to humankind and communities living in the desert:

The beaten earth appears defeated and dead, but it only appears so. A vast and inventive organization of living matter survives by seeming to have lost. The gray and dusty sage wears oily armor to protect its inward small moistness... those animals which must drink moisture get it at second hand—a rabbit from a leaf, a coyote from the blood of a rabbit... the desert, the dry and sun-lashed desert, is a good school in which to observe the cleverness and the infinite variety of techniques of survival under pitiless opposition. Life could not change the sun or water in the desert, so it changed itself... The desert has mothered magic things. (Trimble 17)

Imaginative perception

In “The Wall/Ruin: Meaning and Memory in Landscape” and “Sketching the Landscape,” I talked about how to define imaginative perception and its importance: “[a]n imaginative perception where one forms a conception of the world based on how objects, artifacts, and space relate to our experience” (“Sketching” 13). While imaginative perception is about our ways to interpret places from our immediate experience, collective memory, in turn, “is as varied and dynamic as each individual’s interactions with place, and memories of the past are inextricably intertwined with the embodied phenomenological experience” (Lavoie and Sleipness 80). How do humans inhabit, interact with, and impact the desert by their perceptions and actions? We are inhabiting deserts from perspectives of imaginative perception, collective memory, sensory perception, and perspectives of political pressures, including of water use issues. Trimble highlights about the Great Basin, “In the West, mountains and deserts remain entangled—by geography and biology and by law, in water compacts” (14).

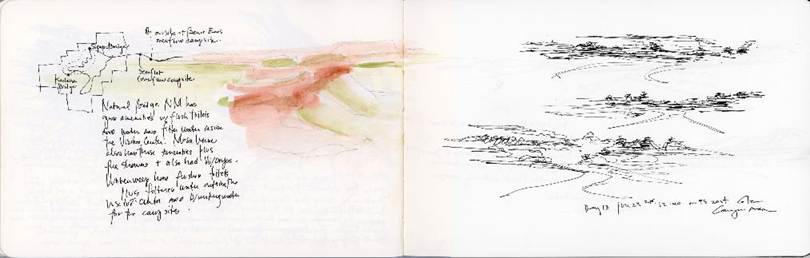

So, what has drawing got to do with it? Drawing on location helps me and others to understand those qualities, internalize them and interpret them with my drawings (see Lavoie, “I Am the Space Where I Am”). Drawing helps explore these human interactions. Drawing distills and preserves collective memories (just as other artforms such as filmmaking may do in a different way). Drawings are perceptions and experiences—representation. I draw landscapes at different scales and different moments in time in order to understand each place beyond its scientific lens. My drawings emerge out of an awareness of place, which in turn engenders an imaginative perception of the space I am in, and collective memories. Through drawing, I form an active visual, physical, and cultural relationship with the land and water (for more on this, see Lavoie, “Sketching”).

The large-scale quality and various states of aridity of the desert can be a source of inspiration, for the imaginary in diverse desert narratives—at both the individual and the collective level. There are different collective memories associated with different communities cohabiting, at the same time or different moments in time, and each developed its relationships with the desert and water. This may be a matter of controversy between environment versus culture, thus of collective memory. Collective memory can be obscured or celebrated in the American West. It is created perpetuated, or erased by individuals and communities, and it expresses the values we put in our landscapes—here, deserts. For some, the collective memories and experiences associated with deserts are empty vessels, for others, deserts are rich in all forms of life with beautiful details; while for yet others, deserts are only there to be fought against because of the harshness of living they present.

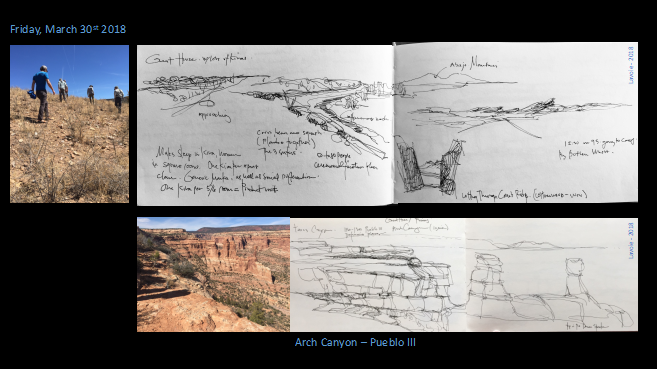

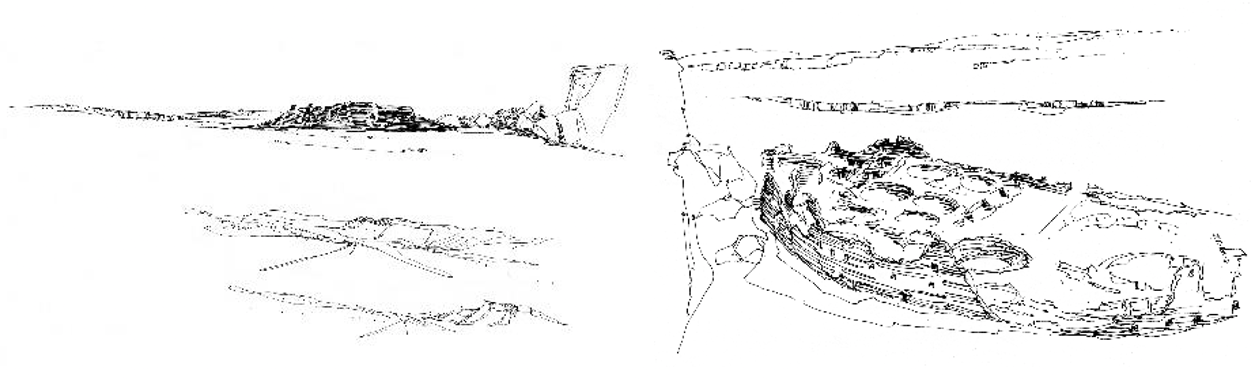

For centuries, environmental and political issues have impacted the cliff dwellers of the Bears Ears National Monument, the Ancestral Puebloans of Chaco Canyon, and the Utah Mormon pioneer communities—where all collective memories relate in some way to water access and land usage. The imaginary, collective memory, and the realities of the Southwest desert environment are a matter of aridity, water, and identity. Figure 8, for instance, illustrates my perception of the highly controversial Bears Ears boundaries, as shown in my drawing journal.

Williams in The Hour of Land highlights one of our dilemmas about the value of wilderness in how our communities can sustain unbridled growth, as experienced especially in the West: “We must change our lives, our politics, our beliefs, our actions, if we are going to survive” (287). As President Trump reduced the size of Bears Ears in 2017, those spaces are controversial, politically charged, and contested. As a designer with a desire for intervention, for me drawing is part of understanding issues at the core. Pierre Nora, in “Between Memory and History: Les Lieux de Mémoire,” emphasizes an important distinction for recollecting memories at controversial places—the distinction between the concepts of “lieux de mémoire” and “milieux de mémoire”:

Our interest in lieux de mémoire where memory crystallizes and secretes itself has occurred at a particular historical moment, a turning point where consciousness of a break with the past is bound up with the sense that memory has been torn—but torn in such a way as to pose the problem of the embodiment of memory in certain sites where a sense of historical continuity persists. There are lieux de mémoire, sites of memory, because there are no longer milieux de mémoire, real environments of memory. (Nora 7)

Nora’s distinction sheds light on and helps to create a framework for what is important to remember and what influences our imagination (Lavoie and Sleipness, 2018). For cliff dwellers of the Bears Ears area, collective memory, place, and identity are defined by water, survival, and cultural traditions; and in their later period, by defensive dwelling. For instance, their dwellings were strategically located on a cliff wall with very difficult access to be safe from intruders. In addition to attackers, however, lack of water may have been another threat that caused them to abandon their cliff dwellings. It is part of the past because the Ancestral Puebloans left centuries ago; it is part of the present because those settlements remain at the same location, where ways of life can be imagined and part of their place-based identity can be experienced. Therefore, Cliff Dwellings of Bears Ears are both “lieux de mémoire” and “milieux de mémoire,” to use Nora’s terms. They can bring multiple interpretations and present-day experiences when one is in this particular desert landscape. At a deeper level, the concept of collective memory changes where “Memory is a perpetually actual phenomenon, a bond tying us to the eternal present; history is a representation of the past” (Nora 8). Bears Ears remains in the realm of memory, not history. Even today, its centuries-old cliff-dwelling culture remains in our imaginary.

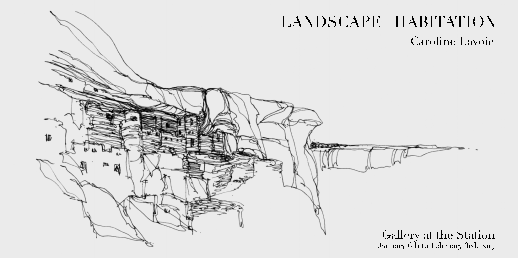

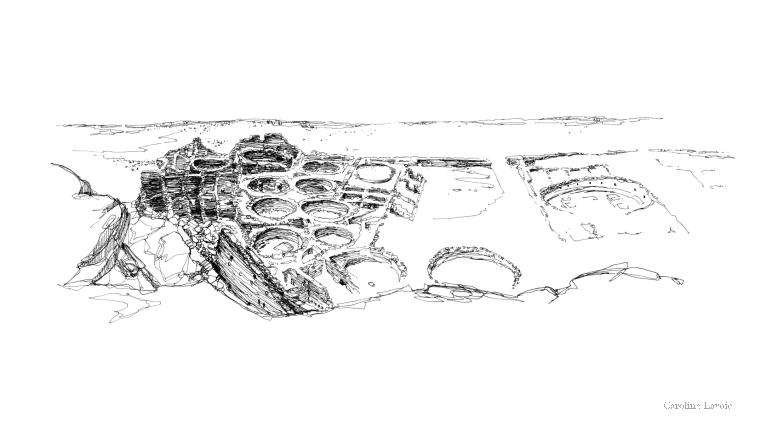

In 2018, I was part of historian and archeologist Andrew Gulliford’s study and conservation group, where I learned about the dwellers’ various phases of defense. Those sites are often hidden and difficult to access, using a series of in-between steps as defensive mechanisms. Figures 8, 9, and 10 are a sample of my visual journey to access those dwellings. A more accessible and preserved cliff dwelling that informs the collective memory can be found in Mesa Verde National Park, a UNESCO World Heritage Site. For the cliff dwellers, those particular dwellings possessed grandeur, remoteness, and mystery (Sagstetter and Sagstetter), and those same qualities remain today in our collective memory of this desert landscape. The drawing of the Cliff Palace at Mesa Verde in Figure 11 evokes these memories and highlights the stark contrast here between landscape and habitation. “Landscape | Habitation” was the theme and title of my exhibition of drawings, in which I depicted the memory of these dwellings.

Water, memory, and community remain inextricable in the desert. In New Mexico and Utah, the collective memory of the Ancestral Puebloans of Chaco Canyon also relates to water. For Utahns especially, water rights and water delivery systems, such as canals, remain at the center of their memories and communities even today. Chaco Canyon’s collective memory is not about defense but about a ceremonial place to come together and meet (from Hovenweep National Monument Utah/Colorado, for instance). Chaco Canyon Ancestral Puebloans moved further south to Rio Grande in New Mexico, and into Mexico. As Wallace Stegner wrote: “Aridity. You may deny it for a while. Then you must either adapt to it or try to engineer it out of existence” (9). This could be witnessed in Chaco Canyon. Its geographic relationship to the Chaco Wash and its relationships to a water source informed its importance as a strategic location (see figure 12). In figure 13, you can see Pueblo Bonito in relation to its natural environment of cliffs, which fell onto Pueblo Bonito many years ago. Standing above the cliff looking down at Pueblo Bonito, I witnessed traces of Chaco’s growth and decline all at once. Several decades of drought may have been the cause of the abandonment of the Chaco settlement (Vivian and Hilpert).

Sensory perception

The drawing in figure 12 shows the view from above the cliff. It offers details of the many once inhabited desert kivas. Part of my drawing process that is important to discuss here is sensory perception (in French, “la perception sensible”) in which the place, landscape—desert, in this context—is perceived in constantly changing conditions. This is a particularly important process for seeing and representing the desert, as it is ever-changing. The light conditions, harsh hot sun, wind, silence, and at times lightening, all push me to try to be in sync with this landscape, to be one with it in a meditative state, if you will. My sensory perception internalizes all these conditions, which are then distilled through my drawings to communicate the essence of the desert as I perceive it—in all its beauty or all its damage.

Sensory perception may be defined as letting our senses be the interface that reacts to and interprets our environment. Furthermore, it is “perception by the senses as distinguished from intellectual perception” (Merriam-Webster dictionary online). In simpler terms, sensory perception means “the act by which the mind receives objects” (“l’acte par lequel l’esprit reçoit les objets”[“Perception,” Multidictionaire 1085]). Additionally, Renaud Barbaras, in La perception: essai sur le sensible, distinguishes two important aspects of perception that help to refine an understanding of the concept. The first is about the discovery of a reality that precedes the “regard”; the second is that perception is sensory, which means that each unique self creates meaning out of the reality. Thus, the reality is established through two sets of filters—one from the senses and one from the interpretation, which is directly linked to one’s experience of a place; in our case, experience of the desert.

As an example of this, the following drawings in figures 14 and 15 visually describe my experience and perception, going through my hands as a visual translation of my sensory perception in the desert. The viewpoints vary from above, from within, or while driving through the desert. The moment in time influences my perception or focus. A rapid gesture captures the sun setting and quickly disappearing at Gooseneck State Park (see figure 14). As seen in this drawing, light is certainly a major element that influences my senses and perception in a phenomenological way, but just as important are scale, water, lighting, wind, and silence, to name a few. In figure 15, a longer moment with the morning sun allowed me to show a greater amount of detail in the geological features and structures of the Gooseneck and the San Juan River. The difference in light informed and enriched my two drawings viewed together.

Among other qualities associated with the desert mentioned above is its vast scale. Your location in the desert is hard to comprehend unless there is a reference point (for example, myself drawing in a place, or visitors to the Grand Canyon who may be experiencing a view from above (see figure 16).

Water, lightning, contrasts

Water in the West is a matter of both survival and human cultures. The desert is marked by our human relationship with water as well as by geological erosion, as can be seen, for example, in Marble Canyon. Seeing and drawing water in the desert also brings awareness of the subtle existence of seasons and the contrasting changes they bring. Experiencing the changing seasons in the desert is unique in that it enriches not just one’s sense of smell, but also our understanding of life in the desert—so well described in Steinbeck’s words earlier. Consequently, drawing and closely observing/perceiving the landscape allows me to highlight the contrasts that the desert brings, from light to scale to smell, involving various senses at once. Some elements can be inspiring, frightening, or limiting at different times. The power of lightning and thunder in the desert, for instance, informs me of the power of this sublime landscape and the powerful and close relationship between the sky and the ground when the lightning occurs. Encountering more than one dangerous lightning storm has led to several unfinished drawings! Island in the Sky in Canyonlands National Park is another powerful desert place where I was lucky to experience those various aspects of desert life: sunny one moment, howling winds the next moment, leading to thunder and lightning on the same day, reminding me how small human beings are in the desert.

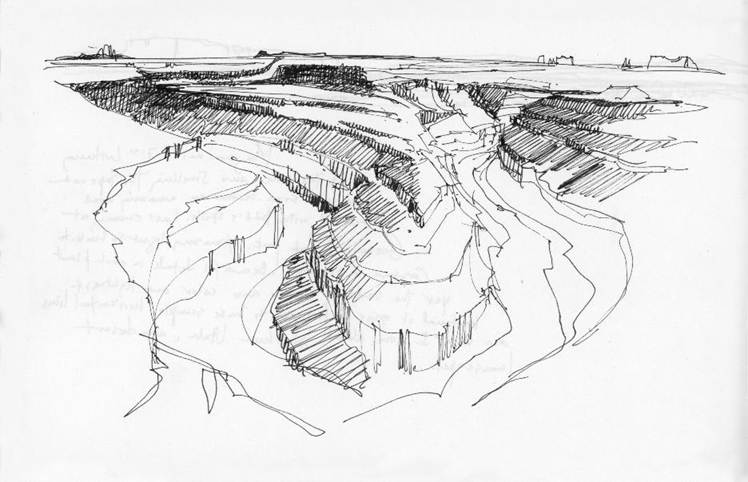

The intense wind in the desert felt while lying on the ground on top of my drawing pad to keep it from flying off is captured in figure 17. The drawing shows limited lines and details, and reminisces of the movement of the wind itself that my drawing hand follows nonchalantly while the other hand holds onto the sketchbook with force. But to capture dramatic desert contrasts such as those experienced in Island in the Sky, the body needs to react to those elements of contrast (wind/calm, water/drought, lighting, geological scale/human scale, as I mentioned earlier). The desert conditions and contrasts generated and initiated my sensory perception and my imaginative perception here.

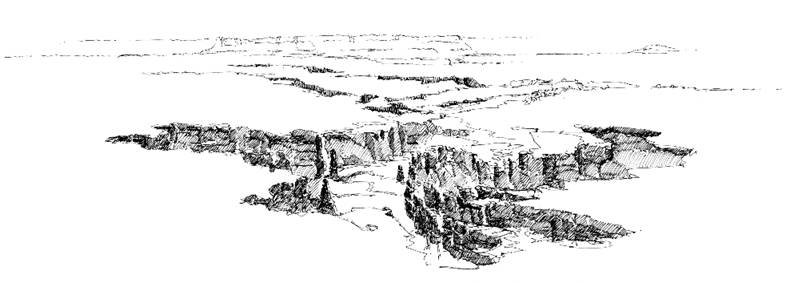

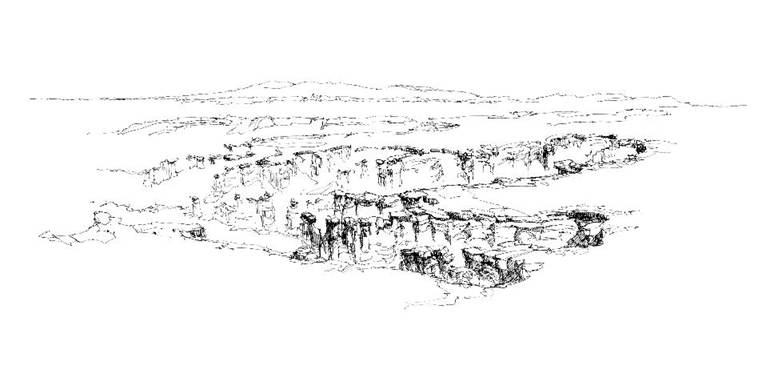

Experiencing the changing reality of the desert can take time. As an artist, it took me over five years to be able to return to the same site in Island in the Sky to capture its essence and to be able to convey this fluid, mutable landscape to others. For some, Canyonlands is a vast land that can be expressed as a simple flat horizontal line. However, its interior is much more complex and reveals its essence (see figures 18 and 19). My drawings show this internal/external relationship. Gaston Bachelard makes a similar distinction between internal and external relationships with his concept of phenomenological roundness:

[W]hen a geometrician speaks of volumes, he is only dealing with the surfaces that limit them. The geometrician’s sphere is an empty one, essentially empty... [I]mages of full roundness help us to collect ourselves, and to confirm our being intimately, inside. For when it is experienced from the inside, devoid of all exterior features, being cannot be otherwise than round. (234-35).

This is like the inside of Canyonlands National Park, which can be seen in figures 18 and 19 with the variation in texture as light informs its essence and my relationship to its vastness, inside and out.

Figures 18 and 19 are both drawings of the Canyonlands desert in the morning that show this close inside/outside relationship and the subjectivity of being in the landscape. Nowhere is this more powerful or evident for an artist or writer than in the desert. In one sense, being at one with the landscape and the wind in Canyonlands, I enter a meditative state in silence when I am drawing the desert.

My drawings are incorporating collective memory into this embodied phenomenological experience. In other words, I am able to capture the essence of qualities of place. Similarly, David Seamon discusses the basis needed for a phenomenological response to place and experience: “Merleau-Ponty argues that the lived foundation of this human-world enmeshment is perception, which, in turn, he relates to the lived body—in other words, a body that simultaneously experiences, acts in, and is aware of a world that, normally, responds with immediate pattern, meaning, and contextual presence” (1-2, emphasis in original). Some writers are able to capture their experience of the desert in their narratives; for me, this means capturing through drawing changes in light and shadow, texture, vegetation, and scale (see figure 20).

Conclusion

As our concepts of place evolve, or change, so too does our concept of the desert. Curtis indicates that “place, like memory, is a work in progress” (Curtis 61). Drawing or viewing drawings of the desert in this context helps all of us establish the link between perception and reality, and to experience the evolution of deserts. Our understanding of desert places is informed by collective memory (imaginative perception) and sensory perception, from the larger scale of things to the smallest speck of sand. In a way, I become a part of the desert and, therefore, drawing reveals that I am also just a speck when I am in the desert (see figure 21). In Erosion, Williams sums it up very well when a friend asks her, “Aren’t you afraid you will be forgotten?” and she responds by saying: “Each of us finds our identity within the communities we call home. My delight in being forgotten is rooted in the belief that I don’t matter in the larger scheme of things, only that I tried my best to be a good human, failing repeatedly, but trying again with the soul-setting knowledge that my body will return to the desert” (3). The phenomenological approach through drawing that I have outlined helps to better map how we are inhabiting deserts as well as our bodies. Drawing and seeing drawings can help reach this state of awareness. The desert invites us all to embrace both the subjective and the phenomenal.

Works Cited

- Bachelard, Gaston. The Poetics of Space [La Poétique de l’Espace]. Translated by Maria Jolas, Beacon Press, 1994.

- Barbaras, Renaud. La perception: essai sur le sensible. Vrin, 2009.

- Bobbé, Sophie, et al., editors. Déserts Américains : Grands Espaces, Peuples et Mythes. Editions Autrement, 1997.

- Curtis, Barry. “That Place Where: Some Thoughts on Memory and the City.” The Unknown City: Contesting Architecture and Social Space, edited by Iain Borden, et al. MIT Press, 2001, pp. 54-67.

- Duban, François. “Entre écosystème et paysage, les paradoxes d’une nature brute.” Déserts Américains: Grands Espaces, Peuples et Mythes, edited by Sophie Bobbé et al. Editions Autrement, 1997, pp. 17-68.

- Lavoie, Caroline. “I Am the Space Where I Am.” Landscapes | Paysages, vol. 10, Summer | Été 2017, pp. 34-38.

- Lavoie, Caroline. “Sketching the Landscape: Exploring a Sense of Place.” Landscape Journal, vol. 24, no. 1, 2005, pp. 13-31, doi:10.3368/lj.24.1.13

- Lavoie, Caroline. “The Wall/Ruin: Meaning and Memory in Landscape.” Landscape Review: An Asian Pacific Journal of Landscape Architecture, vol. 4, no. 1, 1998, pp. 27-28.

- Lavoie, Caroline, and Ole Russell Sleipness. “Fluid Memory: Collective Memory and the Mormon Canal System of Cache Valley, Utah.” Landscape Journal, vol. 37, no. 2, 2018, pp. 79-99, https://doi.org/10.3368/lj.37.2.79

- Nora, Pierre. “Between Memory and History: Les Lieux de Mémoire.” Memory and Counter Memory, special issue of Representations, vol. 26, spring 1989, pp. 7-24.

- “Perception.” Multidictionaire de la langue française, edited by Marie-Éva de Villers, Editions Québec Amérique, 2007, p. 1085.

- Sagstetter, B., and B. Sagstetter. The Cliff Dwellings Speak: Exploring the Ancient Ruins of the Greater American Southwest. Benchmark Publishing of Colorado, 2010.

- Seamon, David. “Merleau-Ponty, Perception, and Environmental Embodiment: Implications for Architectural and Environmental Studies.” Unpublished essay, 2010, https://www.academia.edu/948750/Merleau‑Ponty_Perception_and_Environmental_Embodiment_Implications_for_Architectural_and_Environmental_Studies

- “Sense perception.” Merriam-Webster.com, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/sense%20perception, accessed Jan. 5, 2021.

- Stegner, Wallace. The American West as Living Space. University of Michigan Press, 1987.

- Trimble, Stephen. The Sagebrush Ocean: A Natural History of the Great Basin (10th anniversary ed.). University of Nevada Press, 1999.

- Vivian, R. Gwinn, and Bruce Hilpert. The Chaco Handbook: An Encyclopedic Guide. 2002. University of Utah Press, 2012.

- Williams, Terry Tempest. Erosion: Essays of Undoing. Sarah Crichton Books, 2019.

- Williams, Terry Tempest. The Hour of Land: A Personal Topography of America’s National Parks. Sarah Crichton Books, 2016.

- Zentner, Joe. Monument Valley: Filmmaking and Myth. 1995. https://www.desertusa.com/desert-activity/monument-valley-films.html

About the author(s)

Biographie : Caroline Lavoie est Professeure à l’université de l’état d’Utah aux États-Unis. Elle est architecte paysagiste, urbaniste, artiste et penseuse visuelle. Son travail consiste à reconnecter les gens avec les paysages qu’ils habitent. Le dessin est essentiel à son processus de conception et à la communication avec le public. Elle utilise la pratique du dessin et de la pensée visuelle et l’applique à l’Ouest américain et au-delà. Ses dessins de l’Ouest américain ont été exposés dans des galeries publiques et des établissements universitaires du monde entier : de la Californie, de l’Utah, du Maryland, du Minnesota, du Nevada, de l’Illinois et du Texas, ainsi qu’en Argentine, en Australie, au Canada, en France, au Liban et en Slovénie. Caroline Lavoie possède une maîtrise en architecture de paysage et une maîtrise en planification en études de design urbain de l’Université de Californie du Sud, et une licence en architecture de paysage de l’Université de Montréal.

Biography: Caroline Lavoie is a professor in the Department of Landscape Architecture and Environmental Planning at Utah State University, USA. She is a landscape architect, planner, artist, and visual thinker. Her work involves reconnecting people with the landscapes they inhabit. Drawing is essential to her design process and in communicating with the public. She uses drawing and visual thinking practice as it relates to the American West and beyond. Her drawings of the American West have been exhibited in galleries and academic venues around the globe: in California, Utah, Maryland, Minnesota, Nevada, Illinois, Texas, as well as Argentina, Australia, Canada, France, Lebanon, and Slovenia. She holds a Master of Landscape Architecture and a Master of Planning in Urban Design Studies from the University of Southern California, and a Bachelor of Landscape Architecture degree from the Université de Montréal.