Community in heritage discourse

Abstract: In heritage and museological discourse, community is a pervasive notion, used in relation to professional practice and control of knowledge, public engagement, as well as focus and purpose. This paper examines community as a concept and its use in the cultural sphere, more precisely in the discourse surrounding the museum world since the 1960s. It considers ‘community’ with emphasis on the impact of the ‘New Museology’ which redefined the relation between museums and their ‘communities’, on its use in public policy in Britain and more particularly Scotland since devolution and, more recently, on its connection with activism in museums.

Keywords: Community, Heritage, Museums, Activism, Scotland

Résumé : Dans le discours sur le patrimoine et la muséologie, la notion de communauté est omniprésente, utilisée pour décrire des pratiques professionnelles, les sources et autorité de la connaissance, une approche participative, ainsi qu’en termes de cible et d’objectif. Cet article aborde l’utilisation du concept de communauté dans le domaine culturel, plus précisément dans le discours s’attachant au monde muséal depuis les années 1960. Il explore ce concept à travers l’impact de la Nouvelle Muséologie qui a redéfini la relation entre les musées et leurs ‘communautés’, son utilisation dans les documents relatifs à des politiques publiques en Grande Bretagne, et en particulier en Écosse depuis la dévolution des pouvoirs, et, plus récemment, son lien avec l’idée de militantisme au musée.

Mots-clés : Communauté, Héritage, Musées, Activisme, Écosse

Community is a ubiquitous word in the heritage sphere, notably the museum world. It is part and parcel of discourses, policy statements, and codes of practice framing and regulating heritage. It also underpins the very process of heritage-making which is tightly woven with issues of memory and identity, ultimately fostering a sense of belonging to a given social group.

As Anderson (1983) famously pointed out, the sense of belonging that saturates “community” as a notion is predicated on a shared culture and history which heritage reinforces. He showed how essential heritage (among which sacred sites, preserved buildings), and more specifically museums with which this article is concerned, are in the construction of “imagined communities.” In particular, they act as tools enabling the symbolic representation of nations, the national paradigm being the focus of Anderson’s analysis of the emergence and spread of nationalism. In his words, “museums, and the museumizing imagination, are both profoundly political” (178). They tell a lot about how societies view themselves, reflecting their concerns and priorities.

For a long time, the purpose of museums was to shore up Enlightenment universalist and modernist classification in order to serve grand national and imperial narratives. In the museum, this gave pride of place to ethnographic and anthropological displays with taxonomic conventions that ranked, classified and eventually defined peoples and societies (Bennett). Exhibitions were highly ethnocentric and ultimately centred on an “othering” process, culture being used to legitimise and bolster a vision of the world, cultural and value systems and a social order. Museums fitted in with the Gramscian concept of hegemony, as their role was to present artefacts, images and ideas reflecting a clear power system, with a view to educating citizens and instilling appropriate attitudes and outlooks in them. Within the confines of museums as normative sites, the communities that were imagined tended to be homogeneous and standardised, in accordance with a Western imperialist perspective. Most of all, they adhered to a clear national paradigm: the national community (MacLean; Fladmark).

From the second half of the twentieth century, particularly from the 1960s, this hegemonic role of museums has been questioned, as the museum world was faced with the challenge of responding to socio-cultural and political changes in the post-colonial world that was emerging. With the rise of new independent states as a result of decolonisation, of movements demanding equal rights for women or ethnic minorities, of revolutionary movements in Latin America, of widespread student protest movements, museum activists and professionals started challenging the traditional approach to museum thinking and museographical practices; in the museum sphere, this was spurred on by the growing interest in local heritage and grass-root initiatives—partly in response to the standardisation of culture (Boylan; De Varine, “Ethics and Heritage”). They started thinking not only in terms of collections, expertise and method, but also in terms of how best to be of service to society, in other words, in terms of the community they served, a community more fluid than the “national community.” The evolution in the definition of a museum given by ICOM1 clearly illustrates the shift:

- ICOM’s definition of a museum in 1961: “any permanent institution which conserves and displays, for the purposes of study, education and enjoyment, collections of objects of cultural and scientific significance”

- ICOM’s definition of a museum in 1974: “a non-profit-making, permanent institution in the service of society and its development, and open to the public, which acquires, conserves, researches, communicates and exhibits, for the purposes of study, education and enjoyment, material evidence of man and his environment” (my emphasis).

These questions and challenges gave rise to the “New Museology” whose ultimate aim was to transform museums into more democratic and inclusive spaces (Vergo; Message, New Museums). In particular, but not exclusively, “New Museology” became associated with the community museum and ecomuseum movements, an ecomuseum being defined as a community-based heritage project that supports sustainable development (Davis). Interestingly such museum spaces were described as “processes,” so their emphasis was not on permanent collections, conservation and display, but on their connectedness with the community and environment they served. They were to constantly reassess their content as “tools for adapting the community and its culture(s) to a changing world” (De Varine “Ethics and Heritage,” 228). If this reappraisal arguably still endorses the authority of the museum, it posits “communities,” in its plural form, at the core of the museum’s raison d’être. Therefore, museums have reinvented themselves because the relationship with the communities they serve has changed and their purposes have developed.

The aim of this article is to chart these changes foregrounding three key aspects of the concept of community—a fluid, protean and ambiguous concept—which have been highlighted and resorted to in museum cultural theory over the past two or three decades (Crooke; Watson): firstly, the symbolic dimension of community, secondly community and / in public policy, and finally community and activism. The focus will primarily be on the British Isles with special references to the case of Scotland and, more specifically, Glasgow Museums.

1. The symbolic dimension of community

Museums remain an integral part of the “memory-heritage-identity complex” (MacDonald 5) which is crucial in projecting, buttressing or claiming the sense of belonging of a given community and are more often than not still viewed as a legitimising authority. Whatever their forms and strategy of communication, the narratives museums construct convey feelings of shared experiences, be it in terms of history, culture, socio-economic background, all essential in the development of identity whatever its nature: national, regional, local, related to race, class, age, gender, or disability. As memory media, museums are instrumental in selecting, interpreting, illustrating, objectifying the past to shape collective memory and make sense of past events and historical journeys, of roots and routes or foundational moments and trajectories.

In the process, their narratives may also imply exclusion, as “communities” are anything but univocal; they are multi-layered and complex (Davis 29-32). The questions of who is represented, by whom and who for underlay much of the probing of the “New museology” and the work of critical theorists concerned with heritage in the 1980s and 90s (Karp, Kreamer and Lavine). In England in 1999, the conference entitled “Whose Heritage?” organised by the Arts Council of England, the Heritage Lottery Fund, the Museums Association and the North West Arts Board, is emblematic of this period. Its aim was to interrogate the place of race and cultural diversity in the way heritage was envisioned in the British Isles. It is during this conference that Stuart Hall defined heritage as a “discursive practice,” “reflect[ing] the governing assumptions of its time and context” (Hall 25, 26). It is worth going back over the context of this conference and Hall’s contribution. During the 1990s, heritage had benefitted from increased funding due to the creation of the Heritage Lottery Fund in 1994 which was a non-departmental public body accountable to parliament through the then Department of Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS). Its purpose was to allocate National Lottery proceeds to heritage projects. Its early choices and distribution of funds were critiqued as the “startling redistribution of wealth from ordinary working people to leading Conservatives” (Lowenthal 91) when, in 1995, large sums were used to fund two projects. One was to buy Winston Churchill’s pre-1945 collection of letters and speeches from his descendants and acquire them for the nation; the other was to secure the purchase and management of Mar Lodge estate, an exclusive hunting estate in the Cairngorms in the Scottish Highlands, by the National Trust for Scotland. Within this context, many questions were asked as to the roles and objectives of heritage and its potential for conflict, friction and contest.

In critical theory, heritage came to be associated with “dissonance” seen as “intrinsic to the nature of heritage,” since

all heritage is someone’s heritage and therefore logically not someone else’s: the original meaning of an inheritance implies the existence of disinheritance and by extension any creation of heritage from the past disinherits someone completely or partially, actively or potentially. (Turnbridge and Ashworth 21)

The inherently contested nature of heritage has been the focus of many analyses which explore heritage conflicts and discuss issues of affect, silences and recognition, along with the uses and potentials of difficult pasts such as, in the case of the English-speaking world, the Northern Irish past and the period of the Troubles (Crooke, “Museums, communities and the politics of heritage”), or how to deal with the colonial past and address the legacy of slavery, or how to re-centre indigenous voices in settler nations (Gouriévidis). Making museums more representative of the plural nature of contemporary societies means that they inescapably grapple with issues of community representation and exclusion / inclusion.

2. Community in public cultural policy

As museums are recognised as instrumental in the transmission of identity and culture, and in the education and enlightenment of citizens, they have been long-standing agents of civic reform and social improvement, driven by governments keen to use them to disseminate ideals of nationhood and citizenship. Once used to represent homogeneous national communities, to project Western “civilising” values and exercise social control, they have become instruments mobilised to promote well-being and social cohesion (Boylan, “Targets or Instruments”). From the 1990s especially, “community” has become a buzz-word in the policy documents that have framed the work of museums, conditioning access to funding and grants. It has been argued that museums have experienced “their biggest culture shift in 150 years […] mov[ing] into the age of the ‘social museum’” (Tait 1).

In public policy, in Britain since the late 1990s, “community” has featured prominently and has been married to notions of inclusiveness and social justice. During the Thatcher era and its adherence to free market ideology and restrained government spending, public bodies had to justify their existence in terms of value for money and customer satisfaction. The government led by New Labour and elected in May 1997 did not fundamentally alter this approach when it introduced the concept of “Best Value.” It placed on local authorities a duty to make adequate cultural provision, deliver services to clear standards, and to consult with and involve their users. Nevertheless, the struggle against social exclusion became fundamental to its rhetoric and a feature of its policy. Best value was therefore fused with the discourse of social inclusion and cohesion, social and economic regeneration, and civil renewal. The aim was to build confident, cohesive, tolerant and sustainable communities.

In 2000, the Department of Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS) issued a policy document, Centres for Social Change: Museums, Galleries and Archives for All, which specifically outlined the key role that museums were expected to play in combating social exclusion in its multiple forms and in empowering individuals and communities in the process:

Museums, galleries and archives, with their unique collections, represent one of the most significant cultural resources in the community, and provide a valuable resource for lifelong learning. They can play a role in generating social change by engaging with and empowering people to determine their place in the world, educate themselves to achieve their own potential, play a full part in society, and contribute in transforming its future. (DCMS 8; my emphasis)

In terms of lexis, in this paragraph, “community” seems to blend in with “people” and “society” and is used as an all-encompassing term with little specific focus. It is here to denote the new orientation that museums were to endorse, a radical change that would be implemented gradually. The present and the future were to be the foci for museums, rather than the conservation and preservation of the past. Access, audience and outreach initiatives were encouraged as well as involvement of those at risk of exclusion in the provision of services. Museums were to become more outward looking and “mainstream social inclusion as a policy priority” (DCMS 5, 13). They were to review and revise their practices and methods, train their staff in view of this objective, and forge partnerships with other organisations in order to deliver social inclusion.

In Scotland, since devolution which saw the re-establishment of the Scottish Parliament in 1999, social justice has been a crucial feature of Parliament discourse, presented as a key policy objective to be achieved far more effectively by a devolved government. Social justice has therefore been the nub of much work across all departments, initially in tandem with New Labour’s initiative; this has included sports and the arts which, as devolved matters, are under the responsibility of the Scottish Parliament and comprise national galleries, library and museum collections, as well as the historic environment. In 1999, Donald Dewar, the architect of devolution in Tony Blair’s government and First Minister of Scotland from 1999 until his death in 2000, set out the ambition of the new Parliament in confronting poverty and social exclusion in a document entitled Social Justice… A Scotland where Everyone Matters, in which social justice was said to lie at the heart of political and civic life in Scotland. Social justice and accountability were firmly etched into the discourse that surrounded the “New Scotland” and have played a central part in Scottish political rhetoric, whatever the party in power. Shortly after, in 2000, the then Scottish executive—dominated by a Labour / Liberal Democrat coalition—put forward the first specific cultural strategy devoted to Scotland: Creating our Future… Minding our Past. Scotland’s cultural strategy. If it foregrounded the uniqueness and diversity of Scotland’s culture enriched by “continuous migration,” “a rich, complex blend of the indigenous and the international” (Creating 5), it also highlighted inclusion and the enhancement of people’s life. In the words of Donald Dewar, who provided the foreword: “It is through engagement with culture in its widest sense that people are enabled and communities strengthened. Our approach to culture is therefore inclusive and diverse” (Creating 5). The body dealing with non-national museums, the Scottish Museums Council,2 also issued its own guidance in response to the Scottish government’s strategy reflecting the priorities of the time, Museums and Social Justice. Published in 2000, it is a separate but complementary document to England’s Centres for Social Change which provides similar guidelines for museum services—a blueprint to achieve the goal of social justice.

Thus, increasingly “community” came to dominate the social justice discourse of the newly devolved assembly that partly took its cue from governmental frameworks and policies, a discourse that was to influence museum development, support and objectives, and was endorsed by key agencies in the museum sector. At the UK level, the Museums Libraries and Archives Council—the national development agency for museums, archives and libraries— commissioned a report in 2005, New Directions in Social Policy, to assess the evidence concerning what it labelled six “community areas”: social inclusion, neighbourhood renewal, community cohesion, cultural diversity, health (particularly mental health) and regeneration (Museums Libraries and Archives Council 1). This was the upshot of the Council’s strategic priorities stated in its 2004-2007 plan, which were to contribute to community cohesion, to foster and celebrate diversity, and to ensure accessibility (Museums Libraries and Archives Council 2).

In Scotland, Cornerstones of Communities: Museums Transforming Society (2009) was a report commissioned by MGS in response to National Outcomes set out by the Scottish Government, by then run by the Scottish National Party (SNP).3 It explored the role of museums in creating community cohesion and identity through the study of five venues. Interestingly, it sought to build a picture of those venues’ community profile. What appears strikingly in this report is that depending on the museums’ objectives and location (for instance on tourist routes, in isolated island areas or in the central industrial belt), the notion of community is interpreted differently by informants, confirming its fluid and even slippery status. A museum may therefore serve different communities: inhabitants of a locality, tourists—or even more precisely the Scottish diaspora with local roots—the Gaelic language community in the case of the Highland and Islands, or special needs groups4 (especially through temporary exhibitions). Community may also be linked with activism and take centre stage as the fountainhead of museum creation. Additionally, as a venue, a museum often doubles up as a community hub, furthering sociability and easing the integration of incomers. The report concludes that communities are wide-ranging and highlights two key expressions to define them: local geographic communities and communities of interest. Importantly, this definition was to become a benchmark, taken up in later documents, notably in the first national strategy applied to the museum sector in its entirety (national and other collections): Going Further: The National Strategy for Scotland’s Museums and Galleries, published in 2012 and still in force.

Introduced as a crucial milestone, Scotland’s National Strategy “Going Further” sets out six aims and objectives, the second seeking to “strengthen connections between museums, people and places to inspire greater public participation, learning and well-being” (17). It also reasserts the role of museums and galleries “as focal points for communities and as inclusive spaces where people from different backgrounds can come together” (22) and points out that “the sector contributes to a variety of social agendas—from social inclusion of hard-to-reach groups to health, well-being and social justice” (22).

Placed within the Scottish context, community goes beyond the discourse of social inclusion and has run deep through successive governments’ wide-ranging objectives of achieving a socially engaged Scotland, in particular of fulfilling the professed aims of the SNP’s social democratic programme. Change in museum practice and ethos has largely been fostered by governmental policy in which “community,” or rather “communities,” as a notion has become synonymous with social inclusion and justice as well as people’s participation and engagement. In Scotland, emphasis has been laid on community empowerment because of the nature of the reconvened Parliament and the stamp it wanted to place on its vision. Some of the flagship legislation passed by the Parliament has, for instance, included the 2003 Land Reform (Scotland) Act which dealt with public rights of access to land and community right to buy land, notably enabling community buy-outs in the crofting districts of the northwest and the islands. Another major example is the 2015 Community Empowerment (Scotland) Act whose ambition is to “help to empower community bodies through the ownership or control of land and buildings, and by strengthening their voices in decisions about public services” (Scottish Government 1). In the museum world, engaging with communities and making their voices heard has also led to more participative and militant museum work.

3. Communities, museums and activism

As the social agenda that museums have embraced since the 1990s was extended with calls for greater audience-centred practices, community participation and involvement in decision-making processes along with the necessity for any institution to face up to their social responsibilities and confront prejudices and inequalities, many museums have become socially engaged, taking practical measures to implement this social role, with a view to changing societies and mentalities. Over the past decade, it is a trend which has been both reflected and encouraged through the publications of the Museums Association5 with: in 2013, the report Museums Change Lives that emphasised the point that museums can effect positive social changes benefiting individuals, communities, society and the environment; and in 2018 Power to the People: A Self-Assessment Framework for Participatory Practice, which provided museums with benchmarks to ensure that “museums and communities work together as equal partners”(3).

In this respect, it has become standard practice for museums to develop outreach services taking the museum out into communities. An eloquent example of outreach is the initiative undertaken by Glasgow since 1991—Open Museum. Glasgow’s Open Museum takes “objects from the museum collections out to communities across the city […] in particular communities who may find it difficult to visit [Glasgow’s] museum venues”.6 Its curatorial staff also help “communities’ projects”—events, festivals and exhibitions—and organises talks and activities in “community venues”.7 Community in this sense relates to social groups that do not find their way to museums or feel alienated by museum narratives and artefacts that do not reflect their own identities. Critically, the outreach experience has been rewarding for staff who have had to address their work, collections and approaches to collecting in innovative ways and reassess their methods and ethos. Engaging with communities has also meant engaging differently with the collecting process, the motivations and purpose of collecting, often operating hand in hand with different groups.

Furthermore, beyond inclusiveness and the social value of museums, which are touchstones of museum discourse, what has also become a central notion of critical / theoretical literature also echoed by the Museums Association is activism. It underpins discussions within the museum world and is a priority for many a museum practitioner. Activism is directly associated with a curatorial stance, one that seeks to “represent and often contribute to social and political protest and reform movements. These actions primarily, although not exclusively, take the form of collecting and curating the ephemera and ‘artefacts’ of activist work and, thus, directly or indirectly support such work” (Message, Museums and Social Activism 1). Such curatorial practices have increasingly become mainstreamed; developed in tandem with the rise of social history, they have been the trademark of social and labour history museums since their inception in the 1970s. Glasgow Museums, which is the largest civic museum service in the UK outside London (O’Neill 29), showcases the contrasting history and culture of a city that was once dubbed the second city of Empire thanks to its solid manufacturing and industrial base—notably shipbuilding and iron. Whilst this past economic wealth is reflected in its many impressive public buildings and its collections of art and design, its working-class culture and militancy (but also its high level of poverty and deprivation—which pre-dated and were intensified by de-industrialisation) have found expression in its social history museum, the People’s Palace, particularly since the 1980s, under the aegis of its then curator Elspeth King. More pointedly, in 1987, against the backdrop of Thatcherism with its resulting social convulsions, King curated an exhibition to commemorate the bicentenary of the Calton Weavers’ strike and massacre.8 She also commissioned a series of eight large-scale paintings by Ken Currie that convey the story of the workers’ struggle and picture, for instance, the 1820 Radical Wars, the Rent Strikes of 1915-16, the great depression of the 1930s, the occupation of Upper Clyde shipyards in 1971 and the Miners’ Strike of 1984. They still adorn the domed ceiling of the central gallery of the museum (see fig. 1).

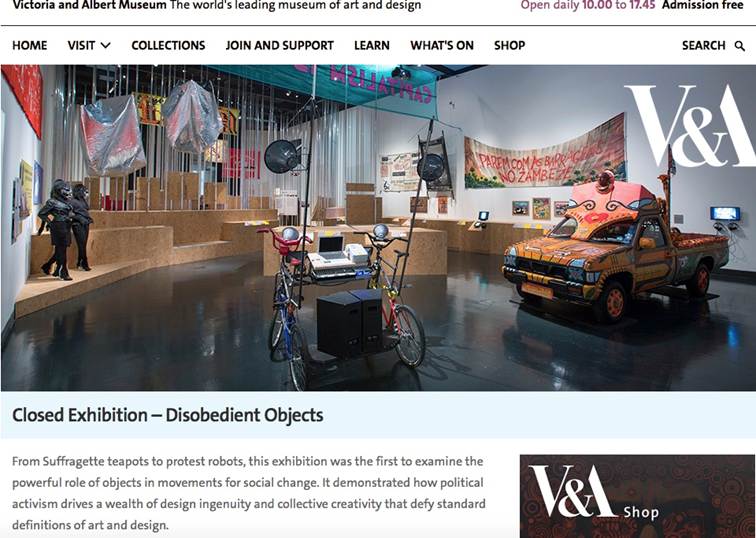

“Radical and populist” (O’Neill 33), this type of approach and collecting strategy has gained currency in many institutions. In 1999, as part of its transport collection, Glasgow Museums acquired a caravan used by anti-nuclear activists at the Faslane Peace Camp on the river Clyde9 alongside documents, images, media coverage and oral histories connected to both the exhibit itself and the Faslane protest; it was restored and placed on display with a four-minute film contextualising it.10 Perhaps more tellingly, in 2014-15, the Victoria and Albert Museum of art and design in London held an exhibition entitled “Disobedient objects” that spotlighted the production and creativity of activist communities around the world and the compelling function of objects in social movements from the late 1970s to the present (see fig. 2).

However, short-lived thematic exhibitions along with the need to renew exhibitions often mean that artefacts symbolising protest and social action are not necessarily the overall sign of an institutional trademark.

The activist museum has therefore also been defined in relation to the challenge it offers to notions of neutrality and impartiality, notions viewed by most museum professionals and theorists with suspicion, given the very origin and development of collections hinging on social Darwinist and colonialist belief systems. In 2007, Richard Sandell, who has long addressed issues of cultural production and representation of minority groups and identities—of community voices all too often marginalised and excluded in the museum realm, prefaced his book, Museums, Prejudice and the Reframing of Difference with the hope that museums

might consider, in some circumstances, substituting their attempts to remain impartial and objective (by presenting diverse, sometimes opposing perspectives on particular issues and leaving visitors to come to their own conclusions) with approaches which privilege (and attempt to engender support for) a particular moral (non-prejudiced) standpoint. (xii)

As already mentioned, many are the venues that have implemented more democratic representations and practices, from threading pluralism and a post-colonial perspective through their narratives to adopting more equitable and open practices in terms of employment, organisational structure and collaborative methodologies, notably involving community practitioners. Some have woven into their mission statements and project objectives the explicit aim of furthering specific social issues. Such is often the case of museums that engage with questions of race, ethnicity or religion, like the Immigration Museum in Melbourne, Australia, whose new permanent exhibition which opened in 2011 places it “as a key site for counteracting racism and promoting social cohesion” (qtd. in Message, Museums and Racism 87) or St Mungo Museum of Religious Art and Life in Glasgow which was expressly conceived “to promote understanding and respect between people of different faiths and those of none”.11 The purpose of those venues is to invite visitors to critically engage with ethical issues and broach subjects which are both sensitive and politicised with a view to undermining stereotypes, talking across differences and combatting inequality and intolerance.

Given museums’ potential as agents of social change and as consciousness-raisers, many are the museum practitioners and scholars who call for even more radical changes. Museums are urged to review their organisational structures and their narratives, in particular those revolving on the paradigm of continual economic (and demographic) growth, on which contemporary societies and public discourse predominantly rely, and concentrate their energies on world issues and the development of an alternative, more sustainable business model (inclusive of their own) (Janes and Sandell 2). With climate change, ecological concerns and the detrimental effects of rampant consumerism becoming ever more pressing issues, museums are encouraged, as some have already done, to marshal their resources in order to promote alternative ideologies, discourses and practices. As knowledge-based and knowledge-shaping venues, museums are ideally placed to make connections between past, present and future, reflecting on past choices, highlighting current challenges and adopting a programmatic approach offering different options in terms of organisation, practice and mission. Activism has been paired with mindfulness to define the future museum, the mindful museum being “a reinvented museum—a mindful organization that incorporates the best of enduring museum values and business methodology, with a sense of social responsibility heretofore unrecognized” (Janes 326). For Janes and Sandell, mindful of such issues as the consequences of the Anthropocene, climate change, “the erosion of trust” and the “unevenness of human rights” (3-6), museums may be placed in awkward positions, as they undertake “a foray into discomfort, disquiet and the unknown” (16) to ensure that they are of benefit to the community they serve and its future, and become “an institution of the commons—a resource belonging to and affecting the whole of a community” (17).

Conclusion

In spite of—or perhaps thanks to—its fluidity and versatility, “community” has long pervaded discourses framing and emanating from the museum world. It is a ubiquitous notion which has gained particular potency in the English-speaking world and notably Britain, especially with the endorsement of the principles of social inclusion and democratic accountability. From the point when museums ceased being viewed as top-down institutions—shapers of cohesive “imagined communities”—and became envisaged, through the New Museological lens, as public spaces where hegemonic values and norms could be disputed and contested and where a variety of viewpoints could be expressed, they were tasked to reflect and engage with the “communities” they served. Whilst community heritage has played a valuable part in post-conflict societies encouraging cross-community contact (Crooke, “Museums, communities and the politics of heritage”), communities have also been essentialised around streamlined representations that strive to pay lip service to the strategies and policy constraints of the discourse of “community.” More recently, in view of the crises confronting contemporary societies—social, environmental, ethical—museums’ engagement with communities has been redeployed into activism.

Yet, recurring calls for community engagement, empowerment and partnership point to challenges and difficulties confronting the museum community itself and the multi-faceted communities it aims to serve, communities that are hardly ever univocal and unified. Acknowledging the diversity of “interpretive communities,” each sharing common repertoires and strategies of interpretation (Hooper-Greenhill 121) means adopting sensitive and flexible methods of curation. It may also mean unsettling long-accepted agendas and interpretive frameworks, a course which has defined the history of museums and museum thinking.

Notes

- 1ICOM (International Council of Museums), created in 1946, is a non-governmental international organisation of museums and museum professionals linked to UNESCO.

- 2Rebranded Museum Galleries Scotland (MGS) in 2008.

- 3The SNP has been in power since 2007, either heading minority or majority administrations.

- 4One of the venues in North Lanarkshire (near Glasgow) mentioned tenants in sheltered housing, Congolese refugee women, school pupils with challenging behaviour, former residents of mental health institutions, members of BME (Black and Minority Ethnic); others mentioned travellers or women who have experienced domestic abuse.

- 5The membership organisation which represents museums and museum professionals throughout the UK.

- 6The team has worked with prisons, care homes and hospitals.

- 7https://www.glasgowlife.org.uk/museums/venues/the-open-museum [Accessed 3/03/2020]

- 8Weavers in the neighbourhood of Calton were involved in a bitter strike over wage-rates and military intervention resulted in the death of three weavers. The event is regarded as an early example of Glasgow’s industrial militancy.

- 9Faslane is the location of Britain’s nuclear submarine fleet.

- 10“Very popular with visitors,” it was last on display at the Riverside Museum—opened in 2011 and home to the transport collection—until it had to be removed for safety reasons because “it was falling apart” (personal communication 3 Mar. 2020).

- 11 www.glasgowlife.org.uk/museums/venues/st-mungo-museum-of-religious-life-and-art. Accessed 2 Mar. 2020.

Works Cited

- Anderson, Benedict. Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. Verso, 1983.

- Bennett, Tony. The Birth of the Museum: History, Theory, Politics. Routledge, 1995.

- Boylan, Patrick J. “Museums and Cultural Identity.” Museums Journal, vol. 90, no. 10, 1990, pp. 29-33.

- Boylan, Patrick J. “Museums: Targets or Instruments of Cultural Policies?” Museum International, vol. 58, no. 4, 2006, pp. 8-12.

- Crooke, Elizabeth. Museums and Community: Ideas, Issues and Challenges. Routledge, 2007.

- Crooke, Elizabeth. “Museums, communities and the politics of heritage in Northern Ireland.” The Politics of Heritage: The Legacies of ‘Race’, edited by Jo Littler and Roshi Naidoo, Routledge, 2005, pp. 69-81.

- Davis, Peter. Ecomuseums. A Sense of Place. Leicester UP, 1999.

- Department of Culture, Media and Sport. Centres for Social Change: Museums, Galleries and Archives for All, DCMS, 2000.

- De Varine, Hugues. “Ethics and Heritage: Decolonising Museology.” ICOM News, vol. 58, no. 3, 2005, p. 3.

- De Varine, Hugues. “Ecomuseology and Sustainable Development.” Museums and Social Issues, vol. 1, no. 2, 2006, pp. 225-232.

- Fladmark, J. M., editor. Heritage and Museums: Shaping National Identity. Donhead Publishing, 2000.

- Gouriévidis, Laurence. Museums and Migration: History, Memory and Politics. Routledge, 2014.

- Hall, Stuart. “Whose Heritage? Un-Settling ‘the heritage’, re-Imagining the Post-Nation.” The Politics of Heritage: The Legacies of ‘Race’, edited by Jo Littler and Roshi Naidoo, Routledge, 2005, pp. 23-35.

- Hooper-Greenhill, Eilean. Museums and the Interpretation of Visual Culture. Routledge, 2000.

- Janes, Robert R. “The mindful Museum”. Curator: The Museum Journal, vol. 53, no. 3, 2010, pp. 325-38.

- Janes, Robert R. and Richard Sandell, editors. Museum Activism. Routledge, 2019.

- Karp, Ivan, et al., editors. Museums and Communities: The Politics of Public Culture. Smithsonian Institution Press, 1992.

- Lowenthal, David. The Heritage Crusade and the Spoils of History. Viking, 1996.

- MacDonald, Sharon. Memorylands: Heritage and Identity in Europe Today. Routledge, 2013.

- McLean, Fiona. “Museums and National Identity.” Museum and Society, vol. 3, no. 1, 2005, pp. 1-4.

- Message, Kylie. New Museums and the Making of Culture. Berg, 2006.

- Message, Kylie. Museums and Social Activism. Routledge, 2014.

- Message, Kylie. Museums and Racism. Routledge, 2018.

- Museums Association. Museums Change Lives. Museums Association, 2013.

- Museums Association. Power to the People: A Self-Assessment Framework for Participatory Practice. Museums Association, 2018.

- Museums Libraries and Archives Council. New Directions in Social Policy: Developing the Evidence Base for Museums, Libraries and Archives in England. Museums Libraries Archives, 2005.

- Museums Galleries Scotland. Cornerstones of Communities: Museums Transforming Society. Museums Galleries Scotland, 2009.

- Museums Galleries Scotland. Going Further: The National Strategy for Scotland’s Museums and Galleries. Museums Galleries Scotland, 2012.

- O’Neill, Mark. “Museums and Identity in Glasgow.” International Journal of Heritage Studies, vol. 12, no. 1, 2006, pp. 29-48.

- Sandell, Richard. Museums, Prejudice and the Reframing of Difference. Routledge, 2007.

- Scottish Executive. Social Justice… A Scotland Where Everyone Matters. The Scottish Executive, 1999.

- Scottish Executive. Creating our Future…. Minding our Past. Scotland’s cultural strategy. The Scottish Executive, 2000.

- Scottish Government. The Community Empowerment (Scotland) Act 2015—A summary. The Scottish Government, 2017.

- Scottish Museums Council. Museums and Social Justice: How Museums and Galleries can Work for their Whole Communities. Scottish Museums Council, 2000.

- St Mungo Museum of Religious Art and Life. www.glasgowlife.org.uk/museums/venues/st-mungo-museum-of-religious-life-and-art. Accessed 2 Mar. 2020.

- Tait, Simon. “Can Museums be a Potent Force in Social and Urban Regeneration?” Joseph Rowntree Foundation, Sept 2008, pp. 1-16.

- Turnbridge, J. E. and Ashworth, G. J. Dissonant Heritage: The Management of the Past as a Resource in Conflict. John Wiley and Sons, 1996.

- Vergo, Peter. The New Museology. Reaktion Books, 1989.

- Watson, Sheila. Museums and their Communities. Routledge, 2007.

About the author(s)

Biographie : Laurence Gouriévidis (Ph.D. St Andrews, Scotland), PR Histoire Britannique 19ème et 20ème siècles, Université Clermont Auvergne (Clermont-Ferrand). Spécialiste d’histoire sociale et culturelle, ses recherches portent sur la relation entre l’histoire et la mémoire, plus particulièrement sur l’étude de la construction sociale du passé et du patrimoine ainsi que sur les discours étayant ces processus. Elle a publié : The Dynamics of Heritage: History, Memory and the Highland Clearances, Aldershot: Ashgate, 2010; Museums and Migration: History, Memory and Politics (dir.), London: Routledge, 2014.

Biography: Laurence Gouriévidis (Ph.D. St Andrews, Scotland) is Professor of Modern British History at Clermont Auvergne University, Clermont-Ferrand. As a cultural and social historian, she focuses on the interaction between history and memory, looking at the ways societies construct their past, their heritage and the discourses surrounding these processes. Her publications include The Dynamics of Heritage: History, Memory and the Highland Clearances, Aldershot: Ashgate, 2010; Museums and Migration: History, Memory and Politics (ed.), London: Routledge, 2014.