E-petitions to the UK Parliament from 2011 to 2019: Volume, Dynamics and Contents of Responses

Abstract: The first petitions to Parliament recorded in the United Kingdom date back to the

fourteenth century. The right to petition has been recognised ever since and has been

used vigorously throughout the country’s history, particularly in the nineteenth century

when it reached its peak. The number of petitions submitted and signatures collected

then fell sharply after the First World War. However, the introduction of digital

alternatives at the turn of the twenty-first century has given new life to this practice,

which has regained considerable popularity but has been the subject of relatively

few studies about the British platform.

Thus, little is known about responses to petitions submitted to the British Parliament

between 2011 and 2019, which this article proposes to address. To do so, this paper

will analyse both rejected and published petitions. It will first focus on rejected

petitions to measure their overall volume, the evolution of the rejection rate of

petitions over time as well as the motives for rejection. It will then consider the

responses provided to petitions reaching the 10.000 and 100.000 signature thresholds.

For replies supplied when petitions collected over 10.000 signatures, length and contents

will be examined. For those achieving over 100.000 signatures, whether debates were

organised or not will be checked, and in case no debate was held, reasons for this

choice will be explained. Remarks about the reliability of data and functioning of

the system will close the conclusions.

Keywords: Petition, Parliament, Statistics, Volume, Rejection, Publication

Résumé : Les premières pétitions adressées au parlement recensées en Grande-Bretagne datent

du quatorzième siècle. Le droit de pétition est reconnu depuis et a été vigoureusement

employé au fil de l’histoire du pays, notamment au dix-neuvième siècle où il a connu

son apogée. Le nombre de pétitions soumises et de signatures récoltées a ensuite fortement

diminué après la Première guerre mondiale. L’introduction d’alternatives numériques

au tournant du vingt-et-unième siècle a cependant donné une nouvelle vie à cette pratique

qui a ainsi retrouvé une vive popularité mais fait l’objet de relativement peu d’études

concernant le système du parlement britannique.

Ainsi, les réponses aux pétitions soumises sur cette plateforme entre 2011 et 2019

sont peu documentées, ce que cet article se propose de faire. Il analysera dans un

premier temps à la fois les pétitions rejetées et les pétitions publiées. Il se concentrera

ensuite sur les pétitions rejetées afin de mesurer leur volume global, l’évolution

du taux de rejet des pétitions au fil du temps ainsi que les motifs de rejet. Elle

examinera enfin les réponses fournies aux pétitions atteignant les seuils de 10 000

et 100 000 signatures. La longueur et le contenu des réponses fournies lorsque les

pétitions ont recueilli plus de 10 000 signatures seront examinés. Pour les pétitions

ayant recueilli plus de 100 000 signatures, on vérifiera si des débats ont été organisés

ou non et, dans le cas où aucun débat n’a été organisé, on expliquera les raisons

de ce choix. Des remarques sur la fiabilité des données et le fonctionnement du système

clôtureront les conclusions.

Mots clés : Pétition, Parlement, Statistiques, Volume, Rejet, Publication

Introduction

In their 2013 article, Böhle and Riehm define a petition as an “asymmetric form of communication between individuals or a group on the one side and an institution on the other side. A matter of concern is forwarded by the petitioner to which the addressee may react” (Böhle and Riehm 1). In the UK, the first known petitions to Parliament date from the fourteenth century with the right to petition recognized both in Magna Carta and the 1688 Bill of Rights. By the seventeenth century, petitions had become a major tool for bringing forward grievances, particularly but not exclusively for those who could not stand or vote for Parliament. At the time, such grievances essentially addressed local or personal concerns but from the 18th century, they increasingly dealt with matters of public policy. Petitioning activity, both submission and signing, peaked in the nineteenth century before decreasing significantly after World War I (House of Commons Information Office 6-7).

E-petitions are the descendants of this tradition. In 1999, the Scottish Parliament was the first to offer an e-petition platform. English local authorities experimented with similar tools from 2004 and the government of Tony Blair implemented its own Downing Street system from 2006. A different platform was then launched from 2011 by the Conservative-Liberal coalition led by David Cameron followed by the version currently in use introduced in 2015. Under this system, British citizens and UK residents are free to submit petitions online via the dedicated Parliament platform. Petitions are then checked for admissibility by the Petition Committee before being opened to signatures on the same site. Petitions receiving more than 10,000 signatures are entitled to a response from the government, while those passing the 100,000 threshold can be considered for a debate in Parliament.

The introduction of the Scottish platform opened the way to multiple works on such initiatives, first on the Scottish system (Macintosh et al; Carman), then on its successors, from Belgium (Contamin, Leonard, and Soubiran) to Finland (Berg), Brazil (Breuer and Farooq) to India (Alathur). The participants in such processes were investigated, be they petitioners (Huang et al.; Bright et al.) or signers (Alexander; Puschmann et al.), as well as the topics of petitions (Hagen et al.; Hitlin) or reasons for success (Cabonce and Cornelio; Cruickshank, Smith). By the time the 2011 Parliamentary system was introduced in the UK, enthusiasm for e-petitions in academia had however declined and there are therefore few publications on this system and on its 2015 version besides the work of Girvin on its democratic potential, that of Asher et al. on its capacity to enhance public engagement with Parliament, that of Matthews on the relationship between e-petitions and Westminster’s MPs or that of Yasseri et al. modelling patterns of signatures through time.

Moreover, if petition outcomes have been investigated, the issue of official response to petitions remains largely unexplored. Indeed, Bochel’s extensive work on the Welsh and Scottish platforms, for instance, gave useful pointers on outcomes, particularly when she emphasized that “for many petitions there can be a range of actions and outcomes, and […] ‘success’ is therefore unlikely to be ‘all or nothing’. Rather, there may be something of a continuum” (Bochel 5). And Leston Bandeira in her study of the British Parliament between 2015 and 2017 identified four roles for e-petitions, namely linkage, campaigning, scrutiny, and policy. Yet, only Wright’s 2012 study of the Downing Street platform deals with the contents of official replies made to petitions, though it is not the main topic of his article.

Thus, little is known about responses to petitions submitted to the British Parliament between 2011 and 2019, which this article proposes to address. In order to do so, here I will analyse both rejected and published petitions. I will first focus on rejected petitions to measure their overall volume, the evolution of the rejection rate of petitions over time, as well as the motives for rejection. I will then consider the responses provided to petitions reaching the 10,000- and 100,000-signature thresholds. For replies supplied when petitions collected over 10,000 signatures, length and contents will be examined. For those achieving over 100,000 signatures, whether debates were organised or not will be checked, and in case no debate was held, the reasons for this choice will be explained. I will close with some remarks about the reliability of data and functioning of the system.

The study presented here will be based on metadata pertaining to the 116,846 petitions published by the British Parliament between July 2011 and July 2019 during the premiership of David Cameron and then Theresa May. For each petition, the data includes whether the petition was accepted or rejected–and, if so, the cause–, a title, a description, a date of submission, the number of signatures collected, and government response, if any. This data was collected by the author on the https://petition.Parliament.uk/ site under an Open Parliament licence allowing its copy, distribution, adaptation, and exploitation for both commercial and non-commercial purposes. Given the volume of data involved, various digital tools were used to help process and analyse it: Open Refine for filtering data according to various criteria, Excel for calculations, Tableau Desktop for data visualisation, and Voyant and AntConc to mine textual data about reasons for rejection of petitions and government responses to petitions. Automated and manual analyses were thus combined, as well as quantitative and qualitative work on the dataset.

Rejected Petitions: Volume, Evolution, and Causes

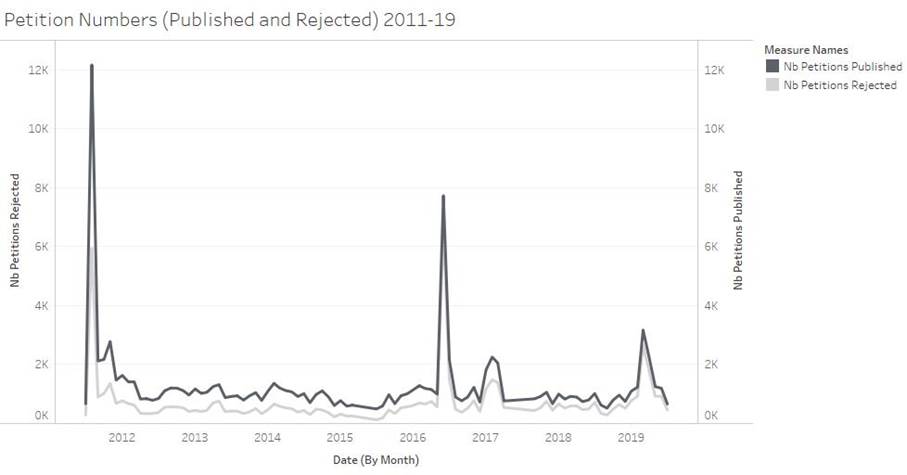

Assessing and comparing the rejection rates of different online petition platforms is a delicate matter as functioning varies from one to another, but a report published in 2015 by the Scottish Parliament gave a figure of approximately 30% for the Canadian, Irish, Scottish and Welsh systems between 2012 and 2015 (Public Petitions’ Committee 44). In the UK, out of the 116,846 petitions published between 2011 and 2019 during the premierships of Cameron and May, 65,762 were rejected, or 56.3% of the total. Logically, as shown on the graph below, the evolution of the number of petitions rejected over this period closely mirrors that of the number of petitions published with peaks in rejections matching peaks in publication.

June 25, 2016, for instance, two days after the Brexit referendum, was the day with the highest number of petitions published (2,540) and the day with the highest number of petitions rejected (2,330), with exceptional figures in both areas from June 24 to 29. Another unusually busy period both for publications and rejections was August 2011, when the Coalition platform was launched months after the Downing Street one had been suspended for the 2010 General Election, followed by riots in London triggered by the death of Mark Duggan, man shot dead by the police on August 4. Another spike is visible on January 30, 2017, the day when Theresa May announced that Donald Trump had been invited to the UK for a state visit, with high levels of activity also in the last week of March 2019 as the deadline for leaving the EU approached. The intensity of the political situation was thus clearly reflected on those days in the exceptional peaks in petition creations and rejections.

It is worth noting, however, that the only petitions whose data is made public by Parliamentary services are published petitions. Yet, a closer look reveals that the number of IDs created does not match the number of petitions published. For the 2011 to 2015 period, for instance, 76,138 petition IDs were generated but only 60,948 petitions were published. Thus, 15,190 IDs (19.9%) did not result in a published petition. For the 2015 to 2017 period, the figure is 65.3% and for 2017-19, 64.6%. While all data pertaining to published petitions is made public by parliamentary services to ensure the transparency and accountability of the procedure, this gap between the number of IDs generated and that of published petitions seems surprising, suggesting that a number of petitions might be discarded before publication without a trace. An answer to an enquiry from the author to the House of Commons’ Petition Committee states that such discrepancies can be due to technical problems leading to the erroneous generation of IDs and to petitions unpublished because they contained defamatory, offensive or extreme content. But the main reason is said to be petitions submitted with under five signatures which are not passed on to the committee for the next stage of the process (verification before publication). This does not apply as extensively to the 2011-15 dataset since 39,899 petitions were published in that period, even though they obtained fewer than five signatures. But there are only 22 of them between 2015 and 2017 and 15 for 2017-19. As data about unpublished petitions is not shared with third parties, it is therefore impossible to tell exactly how many petitions are submitted to Parliament, how many petitions are actually rejected overall, and what the reason for each rejection may be. Lack of public access to such data thus leaves in the dark some elements of the system’s functioning, which is clearly a matter of concern, both from a scientific point of view and a democratic one. The following findings about rejections are thus focused exclusively and necessarily on published petitions, with the overall number of rejected petitions certainly much higher.

The full list of reasons for rejecting a petition is provided on the “How Petitions Work” page of the Parliamentary platform (https://petition.Parliament.uk/help#standards). These twenty reasons are however clustered into six categories in the dataset made available by Parliamentary services: Duplicate, Irrelevant, No-Action, Honours, Fake Name and FOI (Freedom of Information). Among published petitions checked for admissibility before being opened to signatures or rejected, the term Duplicate refers to those which are rejected because they call for the same action as another open petition. The rule is that if a petition asking for a specific action is already open, subsequent ones requesting the same are rejected. For instance, petition number 201053 (Change the law so drivers are required to stop when cats have been run over) was rejected as it was felt to be very similar to petition 200529 (Having knocked over a cat, the driver must legally stop to help/trace the owner). According to a report published by the Petition Committee in 2016, “this avoids splitting support for a cause across multiple petitions. You are more likely to get action on an issue if you sign and share a single petition.” From 2011 to 2019, this was the major cause for rejection (52.3%) of published petitions. Interestingly, the figure was even higher on days with peaks of submissions and rejections, suggesting some mobilizing events prompted users to make similar requests repeatedly. This would clearly seem to be borne out, for example, by the fact that 91.7% of published petitions were rejected as duplicates on June 25, 2016, in the immediate aftermath of the Brexit referendum results.

Only after the introduction of the 2015 version of the platform was a committee dedicated to the management of petitions appointed. Thus, only 6.7% of duplicate petitions have additional details about the reason for rejection for the period between July 2011 and July 2015 as opposed to 99.9% afterwards. When information is provided, it is in most cases the ID or the URL of a petition requesting the same action as the one rejected. For instance, rejection details for petition 54363 (the Leicester Mercury campaign to keep Richard III where he belongs) point to petition 39708 (Keep Richard III remains in Leicester). The petition whose ID is given the most in the details for petition rejection (1,280 occurrences) is petition 134345 (DENY the request for a second EU REFERENDUM). It is followed by petition 133548 (Call a snap general election now that the UK have voted to leave the EU), petition 133618 (Invoke Article 50 of The Lisbon Treaty immediately), and petition 178844 (Donald Trump should make a State Visit to the United Kingdom). Overall, out of the twelve most cited petitions in this section, nine are related to Brexit. Occasionally, the duplicate petition is in fact a revised version of an existing petition; for instance, petition 44040 (Fairness on Child Allowance Cuts). In that case, the message is the following: “Any revised e-petition must be submitted to the ‘Office of the Leader of the House of Commons’ as responsible department to avoid it being rejected as a duplicate”.

The second most frequent motive for the rejection of published petitions is placed under the “Irrelevant” heading (16,679 petitions, or 25%). Here again, as with all other motives for rejection, details regarding petitions for the 2011-15 period are fewer than afterwards. It is also important to point out at this stage that prior to 2015, petitions were directed at the government. Since 2015, they have been addressed to the government and Parliament. It is useful to know this, because petitions deemed Irrelevant are in fact petitions requesting an action which was regarded as falling outside the remit of government until 2015, and of government and Parliament since. The most frequent answer provided is thus: “this issue/matter is not the responsibility of government/Parliament”. When details are provided, most petitioners are advised to submit their request to local authorities or local councillors with 7,142 occurrences of “local” in the 10211 petitions for which details are available. IPSA, the Independent Parliamentary Standards Authority, comes second with 1,177 occurrences, followed by the BBC and the London Assembly. The change in addressee after 2015 did not significantly alter this trend. Other potential interlocutors recurrently mentioned in the details for rejection of irrelevant petitions include the assemblies of Wales and Northern Ireland, the Scottish government and Parliament but also mayors, parties, OFCOM (the UK’s communications’ regulator), ASA (the Advertising Standards Authority) or even football authorities like FIFA or the English Football Association. The tone of such explanations is generally factual, as in the case of petition 1328 (“This is a matter for Transport for London”) or petition 1442 (“It is for individual publicans to decide whether to provide free soft drinks”), but can on occasion be more personal: for instance, the answers to petition 51073 (“I am very sorry to hear about the death of Justin Bowman and our sympathies go to his family and friends”) or petition 118098 (“We were very sorry to read about the difficulties your dad is facing”).

“No-action” is the third most frequent motive for rejection of a published petition (11,636 petitions, 17.7%), meaning that it does not ask for a clear action from the UK Government or the House of Commons. For instance, the answer to petition 4809 (Reduction of Rail Fares) states: “It is not clear what action the petitioner is expecting the Government to take–is the petition asking the train operating companies to reduce fares or the Government to regulate prices?”. The most frequent answer provided in the details for these petitions is thus “Petitions need to call on the Government or Parliament to take a specific action”. The main suggestion is then to start a new petition explaining the request more precisely. Providing additional information on the topic of the petition under consideration is also very widespread as the recurrence of the expressions “you can find” (1,057 occurrences) or “www” (1276) attests. For instance, the answer to petition 112455 (Mobility Scooter speed should be limited to walking pace) is: “There is already a speed limit in place for mobility scooters on pavements. You can find out more about the rules here: https://www.gov.uk/guidance/the-highway-code/rules-for-users-of-powered-wheelchairs-and-mobility-scooters-36-to-46”. The prevalence of URLs helping citizens to find their local councillors (48 occurrences) suggests some petitions classified as No-Action should in fact have been placed in the Irrelevant category, like petition 110932, whose answer was: “The Government and Parliament are not responsible for local roads. If your petition is about local roads in Witney, then this would be the responsibility of your local council. You could contact local councillors about this. You can use this page to find out who the local councillors are and how to contact them: https://www.gov.uk/find-your-local-councillors.” Finally, signing an open petition on the same issue as the one submitted is also frequently suggested, like for petition 113914: “We are not sure what specific action you are asking the Government or Parliament to take on this subject. Polygamy is illegal in the UK. If you want to stop the payment of benefits to people in this situation you could sign this petition: https://petition.Parliament.uk/petitions/108431”.

“Honours” comes fourth in the reasons for rejecting a published petition, significantly behind the other three, with 2,549 petitions, or 3.9% of the total. This refers to petitions asking for someone to be given an honour or to have an honour taken away, like petition 106818 (Revoke the peerage awarded to Michelle Mone as it is without merit) or petition 117130 (security guard in Bromley to be given bravery award). Knighthood is the most frequent honour referred to (476 occurrences) followed by OBE (Order of the British Empire) and MBE, peerage and dame. Accordingly, the most common answers when details are available are “We can’t accept your petition because it asks for someone to be nominated for an honour” and also “We can’t accept petitions about appointments”, often completed by “which includes calling for Cabinet Ministers to be sacked or fired” or “which includes calling for a vote of no confidence.” Theresa May is the personality with the most mentions in the titles of the petitions rejected for this reason (192 + 30 for “Teresa” May), first as Home Secretary until July 2016, and then as Prime Minister. She is followed by Nigel Farage (162), Boris Johnson, David Cameron, Michael Gove, Stephen Sutton (an English blogger known for his fundraising for the aid of teenagers with cancer), Jeremy Hunt, John Bercow, Nick Clegg and Kenneth Dalglish (a Scottish former football player and manager). Like all other rejected petitions, those in this category peaked when submissions peaked too, with names such as Farage and Cameron particularly visible in June 2016, for instance, at the height of the Brexit referendum debates. But smaller increases are also noticeable around specific events like the death of Stephen Sutton in May 2014 or the publication of the Hillsborough tragedy report in September 2012. The latter sparked calls for the removal of honours for Irvine Patnik, the MP for Sheffield Hallam, who had blamed the fans for the disaster, and Norman Bettison, the former Chief Constable of West Yorkshire police.

The “Fake-Name” category was introduced in 2015 and accounts for 471 rejected petitions (0.7%), with “FOI” coming last, with only 5 petitions or 0.007% of the whole. Only 76 petitions in the Fake Name category provide details about the reason why they were rejected, but they suggest that the title of the category, implying that some individuals could submit a petition under an assumed name, may be misleading. Instead, 20 were rejected on the grounds that “We can only accept petitions from named individuals, not organisations” and 19 because “Petitions must be submitted using a full name, i. e. first name and surname”. Others refer to causes not actually related to names at all, like petitions 106491 (Lower the age of smear tests to 21) or 106762 (Review the law into hit & run collisions & charge drivers appropriately), which both received answers stating that they were rejected because they had already been re-started and published. As for petitions 108638 (Change the guilty until proven innocent stance of social services) or 108640 (Test on rapists and murderers rather than innocent animals!!), their authors were asked to make the purpose of their petitions clearer, therefore falling into the No-Action category. Others, like petitions 111999 (Raise more awareness and benefits for Chronic Kidney Disease, Kidney Failure) or 147536 (Hold a General Election in 2017) may have fitted better into the Duplicate category as answers suggested signing other petitions on the same issue, while petition 243798 (Give sixth form students the right to go to Friday prayer) could have been under the Irrelevant heading with an answer pointing to the school’s board of governors.

Finally, the five FOI petitions all received the same answer: “You can find out how to make an FOI request here: https://www.gov.uk/make-a-freedom-of-information-request”. This is a reference to the Freedom of Information Act (2000) making it possible to see recorded information held by public authorities. In this category can be found, for instance, petitions 181058 (Release the reasons for the refusal of Calais minors with family in the UK) and 266950 (Allow Scotland to view the result of the secret independence poll). References to FOI can, however, be found in other categories. Petition 75765, for example, requesting “demographic data for the last 5 years on convicted offenders including ethnicity and creed/faith and distribution of offences across the UK” and classified as No-Action is in fact an FOI petition with information about how to make an FOI request in the answer provided, as was petition 260511 (Release information related to the trial of baseline and related panel) marked as Irrelevant.

Of the 65,762 published petitions rejected between 2011 and 2019, eight were signed by over one thousand people, even though they had been rejected. Seven of them were submitted between 2011 and 2015. Of the eight, five were opened, hence the signatures, but then closed at the request of their creator. Petition 36433 (Justice for riot victims Shazad Ali, Abdul Musavir and Haroon Jahan, who died as they tried to protect their shops from looters during a riot in Birmingham in 2011) was said to have been accepted in error as “The site does not publish petitions relating to individual cases for legal reasons”. For the last two, no explanation is given to clear up why they were opened to signatures despite their rejection. Of the eight, the most signed was petition 30225 (Save the Portland Coastguard Helicopter) with 18,351 signatures.

Petition 69138 (David Cameron and Her Majesty’s Government, Please Save David Cawthorne Haines) was the only rejected petition with details of a government response. David Haines was an aid worker captured by ISIL in 2013. The petition was submitted on September 2, 2014, the day a video showing the execution of an American journalist identified Haines as the next target. It was rejected as a duplicate but the response details stated: “This petition has been closed out of respect for the family of David Haines”. A link was also provided to the official statement of David Cameron on September 14 following the execution of Haines.

A majority of the petitions submitted on the platform of the UK Parliament are thus rejected, and the proportion would probably be much higher if data concerning petitions discarded before the moderation stage were included in the analysis. With such data unavailable, the most common reasons for rejection are the repetition of similar demands, requests falling beyond the remit of Parliament authority or whose purpose was not clear.

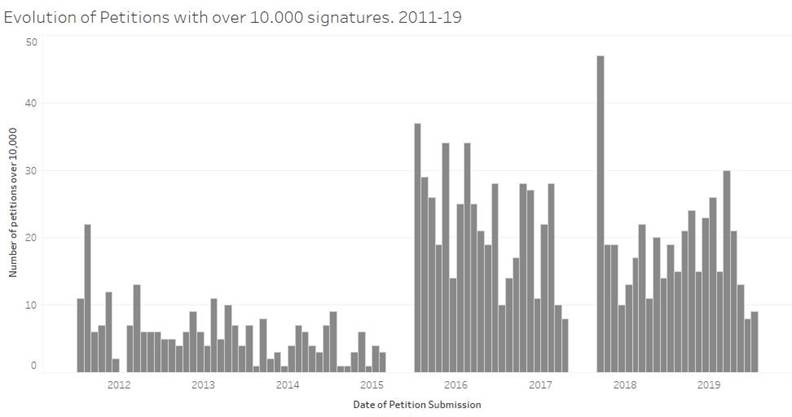

Closed Petitions: Details of Responses

When the coalition platform was launched in July 2011, the only possible response was consideration for a debate in Parliament for petitions reaching the 100,000-signature threshold. But on October 24, 2011, the first response was recorded for a petition gathering over 10,000 signatures. As shown in the graph below, the number of petitions reaching the 10,000-signature threshold increased significantly in the 2015-19 period compared to the 2011-15 one.

Overall, 1% of all petitions published between 2011 and 2019 reached the 10,000 threshold and 2.3% of accepted petitions. From October 24, 2011, when the first response was provided for petitions over 10,000 signatures to the closing of the platform in 2015, 90.6% of petitions over this threshold had details of a response in the dataset. 99.7% did so between 2015 and 2019. During this period, the three petitions over 10,000 signatures which did not get a response from the relevant government department were submitted between May 20 and July 24, 2019 and had the following message recorded: “This petition closed early because of a General Election.” However, nineteen other petitions submitted between those two dates did get a response despite the imminence of the election, thus suggesting that the decision on whether to answer the petition or not was not applied consistently over this period.

No information at all is provided, however, for the 9.4% of eligible petitions for which no response was recorded between October 24, 2011 and 2015, even for petition 73911 (Reinstate Regorafenib on the Cancer Drugs Fund list) which collected 103,841 signatures and could have been considered for a debate. The closure of the site prior to the May 2015 General Election may have played a part in the lack of a recorded response for this petition, even though the 100,000 threshold was passed about a month before. The fact that there is no trace of the Regorafenib drug in Hansard records, apart from a brief question to Parliament from the petitioner’s MP, suggests that no debate was held, though in June 2015 NHS England did reinstate Regorafenib onto the national Cancer Drugs Fund list following a review. What role the energetic #100000voices campaign launched by the petitioner and relayed by various celebrities and newspapers actually played is difficult to assess. What seems clear however is that, if the appointment of a committee dedicated to the management of petitions in 2015 resulted in a marked improvement in the recording of details for petition rejection, this was clearly true as well in the response to petitions which became nearly systematic only after 2015.

In his work on the Downing Street platform, Wright points out that “replies often lacked details” (15), with an average length of 303 words. The average for 2011-15 was 318 in the only column (“government response–details”) providing such information for that period. In 2015 a column “government response–summary” was added. The average word-count for 2015-19 in the details’ column was 402 and 429 when the contents of the two columns is added up, which hints at an increase in response length after 2015.

Between 2011 and 2015, the petition with the shortest answer is petition 43153 (UKIP to be involved in 2015 Televised Debates) with 30,097 signatures and 21 words in the answer. This petition should in fact have been rejected as irrelevant as the response provided was: ‘This is not a matter for Government. The arrangement for party political broadcasts and debates are for the parties themselves.” Petitions 31659 (Put Alan Turing on the next £10 note) and 56810 (The immediate release of Marine A) which come right after petition 43153 in terms of length, should also have been rejected for the same motive. Then comes petition 885 (Put Babar Ahmad on trial in the UK) with 149,470 signatures and 36 words in the answer but no trace either in the dataset or on Parliament’s web page for the petition of the response provided once it had passed the 100,000-signature threshold and only a link to the transcript for the debate. Petition 35788 (Save Childrens’ Cardiac Surgery at the EMCHC at Glenfield Leicester), with 109,306 signatures and 44 words in the answer comes next. The response states that “The Backbench Business Committee have announced that a debate on this matter will be held in Westminster Hall on 22nd October 2012” and that “A Government response will be added to the site in due course.” But no additional response has actually been recorded since. Such a lack of follow-up on recorded responses is recurrent in the 2011-15 part of the dataset and the web pages for the petitions for this period which are derived from the files in json format designed by Parliamentary services. The response to petition 48887 (Call for Government to scrap its plans on childcare ratio changes and undertake a full consultation with practitioners and parents on future proposals) refers, for instance, to an ongoing consultation on the issue and concludes with “We expect to publish a response to the consultation shortly. An update will be posted to this petition once the consultation response has been published.” But no update was added. It is not possible to assess whether the response was actually provided to the petitioner and not recorded in the database, or whether the petitioner received no update at all. The second option would be troubling from a democratic point of view, pointing to issues of potential disparity in the quality of the responses provided to users and consideration for concerns raised by thousands of citizens.

Overall, responses can be brisk dismissals of the request made in the petition. For instance, the response to petition 31250 (RIGHT TO STRIKE FOR POLICE OFFICERS), states that “The Home Secretary has been clear that police officers cannot strike. That is not going to change.” They can rectify a mistaken belief on the part of the petitioner, like petition 49599 (Hands off universal pensioner benefits) stating that “The Government has no plans to remove or means test universal benefits for pensioners.” They can explain that what the petitioner asks for already exists, as does the answer to petition 49086 (Introduce a code of practice for the welfare of domestic rabbits). They can also point to ongoing action on the issue being raised as for petition 23526 (Grant a pardon to Alan Turing) which elicited the following answer: “Lord Sharkey introduced a Private Member’s Bill in the House of Lords on 25th July which would grant a statutory pardon to Dr Turing, and the Government will consider its response to this Bill in due course.”

The longest answer for the 2011-15 period is for petition 70689 (Introduce mandatory noise complaint waivers for anyone who buys or rents a property within close distance of a music venue) with 1,288 words and 43,323 signatures. It concludes that “The Government considers that it is striking the right balance between those who welcome music entertainment and those who have concerns about it”, but provides beforehand a detailed account of the legislation involved. Petition 41702 (Don’t Scrap January A-Level Exams) which comes next in terms of length with 1133 words does not grant the petitioner’s request either but offers an exhaustive background for the decision made by Ofqual, the government department concerned, which triggered the submission of the petition.

Data mining of the responses provided to petitions which passed the 10,000 threshold in the 2011-15 dataset, reveals that 89.5% of them are introduced by the following sentence or a version of it: “As this e-petition has received more than 10,000 signatures, the relevant Government department have provided the following response”. This accounts in part for the fact that “government”, “petition”, “signatures” and “department” are the most used terms in the responses for that period. Moreover, 67.7% of responses contain the sentence: “This e-petition remains open to signatures and will be considered for debate by the Backbench Business Committee should it pass the 100,000-signature threshold”, with “committee”, “business”, “debate”, “backbench”, “open”, “considered”, “pass” and “threshold” also at the top of the list of the most recurrent terms.

Besides such formulaic responses, “Government” can also be found together with constituents such as “has no plan”/“no intention”, “does not plan”, “does not support” to indicate that the government doesn’t intend to grant the request made in the petition. Answers may acknowledge the point being made as demonstrated by the prevalence of clusters like “the government recognises”, “the government is aware”, “the government agrees that”. They may suggest that the issue being raised is not ignored by the government as suggested by the fact that “government” also collocates with the lemma “commit”. And the recurrence of the phrases “the government believes”, “the government’s approach”, “the government’s current position”, or “the government’s view” points to answers presenting the government’s current position on the issue being raised.

When petitions are submitted on similar topics, answers can be copied and pasted, in part or totally. The following paragraph, for example, can be found in responses to petitions 51469, 64331 and 74830:

The Government encourages the highest standards of welfare at slaughter and would prefer to see all animals stunned before they are slaughtered for food. However, we also respect the rights of the Jewish and Muslim communities to eat meat prepared in accordance with their religious beliefs. The Prime Minister has confirmed that there would be no ban on religious slaughter in the UK.

Of the 134 petitions whose answer contained the mention that it would be considered for debate by the Backbench Business Committee should it pass the 100,000-signature threshold, 19 did pass the 100,000 threshold: yet details about an actual debate being organised are provided for only one of them. After verification in Hansard and the online British press, 16 out of 18 indeed resulted in a debate, such as, for instance, petitions 60164 (No to proposed increase in fees for Nurses and Midwives) or 49528 (Ban the sale of young puppies & kittens without their mothers being present). But there is no mention of these debates in official records for these petitions, once again raising the issue of the reliability of the information recorded for the 2011-2015 period. For petitions 56810 (The immediate release of Marine A) and 71455 (Refusal of Cervical Screenings), no details of a debate were provided and no traces of a debate could be found despite them passing the 100,000-signature threshold. Although the decision to organise a debate or not is not systematic and is left to the discretion of the backbench committee, the fact that no response is recorded besides the one provided after the 10,000-signature threshold was passed hinders the scrutiny of the process and in particular, the capacity to provide a complete and systematic assessment of petition outcomes.

The most frequent terms used in responses to petitions which gathered 10,000 signatures or more can help understand the responses provided. Some, like “police” or “funding” point to issues being raised time and again over the period, while others like “cancer” or “screening” are in fact mentioned for only a handful of petitions but used repeatedly in the responses provided for those petitions. Overall, the exercise highlights the potential of text-mining for trying to get a better grasp of large-volume corpora but also its limits, with recurrent, formulaic passages easier to identify than ones with more semantic variety.

In the 2015-19 dataset, the introductory sentence mentioned above disappeared, but from 2015 responses were signed by the department providing the answer, with the most frequent collections of successive words or ngrams being Department of Health, Environment, Food and Rural Affairs, Home Office, Department for Education, and Department for Transport. Petition 119328 (Prevent Obama From Speaking In Westminster Regarding The In/Out Referendum) had the shortest answer (34 words) which stated: “It is an established convention that members of either House can invite whoever they wish and in whatever capacity, to Parliament, to discuss and speak on a wide range of issues. Leader of the House”, while the answer to petition 125827 (The repeal of the code on farming chickens for meat + farming should be debated) contained the following sentence: “We have the highest standards of animal welfare in the world and no changes were ever planned to the animal welfare legislation upholding them, or to the strict enforcement and penalties that apply.” The longest answer with 925 words is provided for petition 108782 (The DDRB’s [Review Body on Doctors’ and Dentists’ Remuneration] proposals to change Junior Doctor’s contracts CANNOT go ahead). In the context of a severe crisis between the government and junior doctors, the response detailed its four reassurances to the profession.

Among the 50 most used words in responses for petitions over 10,000 signatures, 30, i. e. 60%, are the same for 2011-15 and 2015-19, with the word “government” topping the list in both cases. Words and phrases collocating with “government” emphasize the same types of answers with the government in turn or simultaneously stating its refusal to grant the request formulated in the petition, its commitment to the issue being raised, its acknowledgement of the issue and understanding for its importance and pointing to its ongoing position on the topic. Evidence of partly copied and pasted responses on the same issues can also be found: for instance, for petitions requesting the creation of a new public holiday, such as petitions 112392, 123324, 221860, 150516, 220501 or 223013.

The term with the highest level of occurrences in 2015-19 but less present in the 2011-15 dataset is, unsurprisingly perhaps, “EU” (780), clearly due to the 2016 Brexit referendum and following discussions about leaving the European Union. “Health” is less present but “NHS” (756) reflects the persistence of the topic in responses and presumably petitions over this period, while the increasing presence of the terms “children” (516), “[n]-year-olds” (74) and “schools” (509) points to rising concerns in this area. The high figures for “evidence” (445) and “guidance” (397) imply the increased provision of references to justify the position defended in the response.

Responses to Petitions with over 100,000 Signatures

Regarding petitions which passed the 100.000 threshold, there were 180 between 2011 and 2019, i. e. 0.15% of all published petitions over this period and 0.35% of accepted petitions. These could thus be considered for a debate in Parliament. Such petitions received an answer when they reached the 10,000-signature threshold but this response could be completed afterwards. A column entitled “Overview”, for instance, provides information about why a petition with over 100,000 was not debated in Parliament. Hence, 14 petitions which had reached the necessary threshold were not debated because the committee felt a debate on the same issue had been organised recently. Five did not get a debate because the action they were calling for was no longer achievable once the petition reached the threshold. Out of those five, three received the following answer: “The committee decided not to schedule a debate on this petition because the UK has now left the European Union”. Four were not debated because they should in fact have been rejected as irrelevant. Two of those (104471 and 121152) called for a vote of no confidence in David Cameron and Jeremy Hunt, one (122946) called for a General Election to be held in 2016 and another (505446) for Benjamin Netanyahu to be arrested for war crimes when he arrived in London for a visit. Petition 208776 (Abolish the subsidy on food and drink in the Palace of Westminster restaurants) was not debated because “the petition is based on a misunderstanding” and petition 236874 (Laws to be introduced on social networks on hate preaching against religion(s)) received the following comment: “The Committee decided not to schedule a debate on this petition at this stage as it will be considering the issues it raises as part of ongoing work into tackling online abuse.”

For 84 petitions which were actually debated, a link to research briefings was provided. Research briefings are summaries of key issues, legislation, and debates in various policy areas designed to help MPs understand complex issues and inform their work. And indeed, gathering information on the issue raised in petitions is also part of the response provided by Parliamentary services. Besides research briefings, Leston-Bandeira lists initiatives from the Petition Committee such as web forums, face-to-face meetings between MPs and members of the public and online discussions (430) meant to collect evidence and testimonies so as to lay the groundwork for the debates which follow.

For 141 petitions, a link to a debate transcript and to the video for this debate is provided. As 42 URLs were used more than once, it shows that debates were sometimes held in answer to groups of petitions on a similar topic. For example, the debate held on January 14, 2019 was in response to seven petitions: petitions 229963, 221747 and 235185, relating to leaving the EU without a withdrawal agreement; 232984 and 241361 relating to holding a further referendum on leaving the EU; and 226509 and 236261 relating to not leaving the EU. A debate on leaving the EU was also organised on October 17, 2016 in answer to six petitions and another debate on December 11, 2017 to address the possibility of a referendum on the deal for the UK’s exit from the European Union requested in four different petitions. While petitions regarding the EU were the most likely to be grouped for common debates, the practice was not limited to this issue as is shown, for instance, by the debate organised in July 2019 on the BBC licence fee in answer to petitions 234627, 234797 and 235653. Interestingly, grouped debates were also organised in answer to petitions which did not individually reach the 100,000-signature threshold. For example, the debate of July 2018 on the issue of visas for families of British citizens visiting the UK was triggered by petitions 201416 (6,730 signatures), 206568 (71,178) and 210497 (14,297).

More broadly, ten petitions had a link to the video for a debate provided even though they had not passed the 100,000 threshold. Two of them, like the grouping above, were actually close to the threshold at 99,909 signatures for petition 104796 and 89,802 for petition 219558. In four other cases, the link pointed to a debate in the House of Commons on the same topic but with no relation to the petition. And in four cases, the decision was made by the committee to hold a debate even though the threshold had not been reached. For instance, for petition 207616 (Insurance should be on the car itself instead of the individuals who drive it), the initial response given by the Department for Transport when the petition had reached 10,000 signatures had been the following: “The Government has no plans to change the motor insurance system to require vehicles themselves, rather than the use of a vehicle, to be insured.” A response which Susan Elan Jones, who presented the petition during the debate on behalf of the committee, described as “pretty trenchant […], in fact, very trenchant” (Hansard 1) and not doing justice to the “specialist solution to a range of problems relating to car insurance” mentioned in the petition. Hence the decision to hold a debate despite only 60,448 signatures collected. Petitions 200000 (Make British Sign Language part of the National Curriculum), 229744 (Increase college funding to sustainable levels—all students deserve equality!) and 221033 (Prevent avoidable deaths by making autism/learning disability training mandatory) also resulted in a debate despite not passing the 100,000 mark. Overall, 152 petitions were debated over the period between 2011 and 2019, i. e. 0.13% of published petitions.

Conclusion

Analysis of the petitions submitted to the British Parliament between 2011 and 2019 thus suggests that the odds of a petition receiving an official reply are infinitesimal. Over half of published petitions are rejected by Parliamentary services, but this figure conceals a high volume of petitions which are cast off before publication. That no data should be available on the volume of unpublished petitions or on the motives for their non-publication is clearly prejudicial from a scientific point of view but also in terms of the transparency of the functioning of the entire system.

A study of published petitions, however, makes it possible to get a better understanding of the dynamics of rejection as well as their causes. Peaks in rejections matched peaks in publications, with higher levels of rejections when the platform was extraordinarily busy around key events, and a category like “Honours” seeing spikes at a micro level. Most rejected petitions fell into the “Duplicate” category with “Irrelevant”, “No-action”, “Honours”, “Fake Name” and “FOI” coming behind this in descending order.

Among the conclusions which could be drawn from a closer analysis of the rejection details provided in the dataset are the following:

- Most duplicated petitions were Brexit-related, as were the days with the most duplicates.

- A majority of petitions deemed irrelevant, i. e. outside the perimeter of action of government and Parliament, were requesting initiatives falling within the remit of local authorities.

- When the action requested by petitioners was not deemed clear enough, they were encouraged to start a new petition, consult documents on the matter raised or sign an existing petition on a related topic.

- Petitions asking for an honour to be given or taken away mostly mentioned knighthoods and Theresa May.

- The Fake Name category did not actually contain petitions submitted under assumed names but mostly those submitted by organisations or lacking the full name of the petitioner.

- FOI petitions were very few in number and pointed petitioners to a separate procedure.

- Overall, evidence of miscategorised petitions could be found as well as instances of petitions open to signatures despite their rejection.

Regarding replies to petitions reaching the 10,000-signature threshold, their length seemed to be in relation to the willingness of the answering department to provide details rather than the actual number of signatures collected by the petition. Replies could include dismissals of the request made in the petition, acknowledgement of the issue, presentation of government policies, rectification of a mistaken belief or even information that the matter being raised had already been solved or was in the process of being addressed. Copied and pasted answers on similar topics could be found as well as repeated formulaic statements on procedure. While a debate was held for most petitions eligible for one, debates were on occasion denied when a recent debate on the same issue had been recently organised, when the request was no longer achievable once the petition had reached the 100,000 threshold or because they should in fact have been rejected at the beginning of the procedure. A small number of petitions which had collected over 100,000 signatures did not result in a debate without any explanation provided for the decision. Conversely, debates were sporadically organised for petitions which had not reached that threshold on the decision of the petition committee. Finally, debates could be organised as a result of a single petition but instances of grouped debates addressing an issue raised in several petitions were recurrent. Consistency in petition treatment thus seemed variable, even if the appointment of a committee to deal with responses to petitions after 2015 significantly improved the situation.

It seems worth pointing out that the record-keeping of petition data from 2015 was much more comprehensive and reliable than over the 2011 to 2015 period. Lack of details for the rejection of petitions, lack of follow-up on petition response, lack of information on whether the petition resulted in a debate or not, number of petitions eligible for a response or a debate not getting any, or the opening of rejected petitions to signatures were all much rarer after 2015.

When Wright released his study on the Downing Street petition platform, he expressed his surprise and concern for the lack of empirical research on such a popular system (Wright 2). Over ten years after his article was published, this conclusion still applies to its Parliamentary version introduced in 2011, confirming Smith’s belief in the need for more systematic evaluations of democratic innovations. Indeed, even though the novelty of petition platforms has waned, they remain prominent tools of participation and mobilisation, all the more so in the UK where the Parliamentary system has reached record highs in recent years both in terms of submissions and signatures, and where creating or signing petitions was listed as the favourite online political activity, together with watching politically-related videos by the latest version of the Hansard audit of political engagement (Hansard 28). In this process, the release of data for research under open licences and the rising availability of data mining and visualisation tools are precious. While the distant reading of big data (Moretti) doesn’t replace the close, manual processing of documents, it can nonetheless offer a useful overview of the complete data available on a given subject rather than a representative sample, and thus facilitate the scrutiny of democratic innovations essential for science and society.

Bibliography

- Alathur, Sreejith, et al. “Citizen Participation and Effectiveness of E-Petition: Sutharyakeralam ‐ India”. Transforming Government: People, Process and Policy. vol. 6, Oct. 2012, pp. 392-403.

- Alexander, Diane. The Economics of Signing Petitions Social Pressure versus Social Engagement. UC Berkeley Thesis, 2009.

- Anonymous. “Car Insurance Debate”. Hansard, vol. 637. March 5, 2018.

- Asher, Molly, et al. “Do Parliamentary Debates of E-Petitions Enhance Public Engagement with Parliament? An Analysis of Twitter Conversations”. Policy & Internet, vol. 11, no. 2, June 2019, pp. 149-71.

- Berg, Janne. “Political Participation in the Form of Online Petitions: A Comparison of Formal and Informal Petitioning”. International Journal of E-Politics, vol. 8, no. 1, Jan. 2017, pp. 14-29.

- Blackwell Joel, Fowler Brigid, Fox Ruth, Audit of Political Engagement 16, Hansard Society, 2019.

- Bochel, Catherine. “Petitions: Different Dimensions of Voice and Influence in the Scottish Parliament and the National Assembly for Wales”. Social Policy & Administration, vol. 46, no. 2, 2012, pp. 142-60.

- Bochel, Catherine. “Petitions Systems: Contributing to Representative Democracy?” Parliamentary Affairs, vol. 66, no. 4, Oct. 2013, pp. 798-815.

- Bochel, Catherine. “Petitions Systems: Outcomes, ‘Success’ and ‘Failure’’”. Parliamentary Affairs, vol. 73, no. 2, Apr. 2020, pp. 233-52.

- Böhle, Knud, and Ulrich Riehm. “E-Petition Systems and Political Participation: About Institutional Challenges and Democratic Opportunities”. First Monday, vol. 18, no. 7, June 2013.

- Breuer, Anita, and Bilal Farooq. “Online Political Participation: Slacktivism or Efficiency Increased Activism? Evidence from the Brazilian Ficha Limpa Campaign”. SSRN Scholarly Papers, 1 May 2012.

- Bright, Jonathan, et al. « Origines et impacts des hyper-utilisateurs et hyper-utilisatrices en cyberdémocratie. Le cas du pétitionnement en ligne ». Participations, vol. no. 28, no. 3, 2020, pp. 125-49.

- Cabonce, Angelo Bill, and Cyril Jude M. Cornelio. “Pa-Fansign Please! An Experiment on the Effects of the Presentation of Social Causes in Acquiring Support in Online Petitions”. Communication Research International Conference, Jan. 2019.

- Carman, Christopher. Assessment of the Scottish Parliament’s Public Petitions System, 1999-2006. Report, Scottish Parliament, 30 Oct. 2006.

- Contamin, Jean-Gabriel Thomas Léonard, Thomas Soubiran. “Les transformations des comportements politiques au prisme de l’e-pétitionnement. Potentialités et limites d’un dispositif d’étude pluridisciplinaire”. Réseaux, no. 204, 2017, p. 97-131.

- Cruickshank, Peter, et al. “Signing an E-Petition as a Transition from Lurking to Participation”. Electronic Government and Electronic Participation Conference, 2010.

- Girvin, Carys. “Full of Sound and Fury: Is Westminster’s e-Petitioning System Good for Democracy?” Democratic Audit Blog, London School of Economics and Political Science, 19 Nov. 2018.

- Hagen, Loni, et al. “E-Petition Popularity: Do Linguistic and Semantic Factors Matter?” Government Information Quarterly, vol. 33, no. 4, Oct. 2016, pp. 783-95.

- Hitlin, Paul. “‘We the People’: Five Years of Online Petitions”. Pew Research Center: Internet, Science & Tech, 28 Dec. 2016.

- House of Commons’ Information Office. “Public Petitions”. Procedure Series, no. 7, August 2010.

- Huang, Shih-Wen, et al. “How Activists Are Both Born and Made: An Analysis of Users on Change.Org”. Proceedings of the 33rd Annual ACM Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, ACM, 2015, pp. 211-20.

- Leston-Bandeira, Cristina. “Parliamentary Petitions and Public Engagement: An Empirical Analysis of the Role of e-Petitions”. Policy & Politics, vol. 47, July 2019, pp. 415-36.

- Macintosh, Ann, et al. “Digital Democracy through Electronic Petitioning”. Advances in Digital Government: Technology, Human Factors, and Policy, edited by William J. McIver and Ahmed K. Elmagarmid, Springer US, 2002, pp. 137-48.

- Matthews, Felicity. “The Value of ‘between-Election’ Political Participation: Do Parliamentary e-Petitions Matter to Political Elites?” The British Journal of Politics and International Relations, vol. 23, no. 3, Aug. 2021, pp. 410-29.

- Moretti, Franco. Distant Reading. Verso. 2013.

- Public Petitions’ Committee. “Review of the Petitions Process”. SP Paper, no. 859. Scottish Parliament. 2015.

- Puschmann, Cornelius, et al. “Birds of a Feather Petition Together? Characterizing e-Petitioning through the Lens of Platform Data”. Information, Communication & Society, vol. 20, no. 2, Feb. 2017, pp. 203-20.

- Smith, Graham. Democratic Innovations: Designing Institutions for Citizen Participation. Cambridge UP, 2009.

- Wright, Scott. “Assessing (e-)Democratic Innovations: ‘Democratic Goods’ and Downing Street E-Petitions”. Journal of Information Technology & Politics, vol. 9, no. 4, Oct. 2012, pp. 453-70.

- Yasseri, Taha, et al. “Modeling the rise in Internet-based petitions”. 2014, file:///C:/Users/hp/Downloads/Modeling_the_Rise_in_Internet-based_Petitions.pdf

About the author(s)

Biographie : Géraldine Castel est maître de conférences en civilisation britannique à l’université Grenoble Alpes. Sa thématique de recherche principale est la politique britannique, et plus particulièrement la communication et l’activisme en ligne. Elle a travaillé sur les stratégies électorales déployées sur internet par les partis britanniques ainsi que sur l’utilisation d’outils numériques pour faire campagne. Cet accent placé sur le volet numérique de l’action politique l’a conduite à s’intéresser aux méthodes de collecte, de stockage et d’analyse de données numériques et à intégrer progressivement le champ des humanités numériques en complément de son approche civilisationniste. Elle coordonne actuellement un projet portant sur les pétitions en ligne soumises via les plateformes des parlements britanniques et écossais et celles d’opérateurs privés du secteur.

Biography: Géraldine Castel is a senior lecturer in British civilisation at Grenoble Alpes University. Her main research area is British politics, with a particular focus on online communication and activism. She has worked on the electoral strategies adopted by British parties on the internet and on the use of digital tools for campaigning. This focus on the digital side of political action has led her to take an interest in methods for collecting, storing and analysing digital data and to gradually integrate the field of digital humanities as a complement to her work in civilisation. She is currently PI for a project studying online petitions submitted via the platforms of the British and Scottish parliaments and those of private operators in the sector.